Introduction: The Challenge of Defining Systemic Racism

How do we begin to discuss systemic racism? Often these discussions have a confusing overlap of different definitions, with unspoken assumptions about how the world works. Economists often avoid these discussions because the discussions can swing from the external world (laws, programs, and regulations) to the internal (thoughts, beliefs and values) within the same conversation. Economists tend to be far more comfortable sticking with discussions that can be empirically measured and tested rather than investigating the “black box” of a person’s innermost thoughts and ideas.

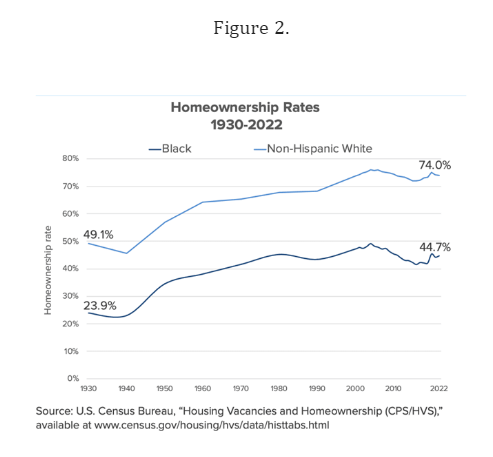

The first order of business, then, is to clarify a working definition that can be used to examine concrete examples of systemic racism. I use that definition- based on historical laws and policies-to examine examples that occurred in the U.S. housing market up to the late 1960s. After the legal reforms of 1968, I argue that newer housing policies that aim to combat systemic racism have outcomes that mirror past racist policies, another example of the law of unintended consequences. As a result, gaps in household ownership remain stubbornly large between Black and White families.

In the end, we economists are generally more interested in examining external outcomes than internal motives. Whether or not the regulations are deliberately racist or end up hurting Black families “as if” they were, this distinction is immaterial to the Black family struggling to get a foothold into the American Dream of owning a home. It is on these grounds of outcomes, rather than intent, that we must judge the housing policies’ final impact.

Creating a Conversation: A Working Definition of Systemic Racism

As an example of the confusing variations in definitions, preeminent scholars Massey and Denton (1993) describe systemic racism as a type of racial discrimination that can affect institutional structures, social structures, individual mental structures and everyday interaction patterns. Braveman, et. al. (2022) argue that systemic and structural racism are often used interchangeably, to mean “involvement of whole systems, and often all systems—for example, political, legal, economic, health care, school, and criminal justice systems (that also include) laws, policies, institutional practices, and entrenched norms.”

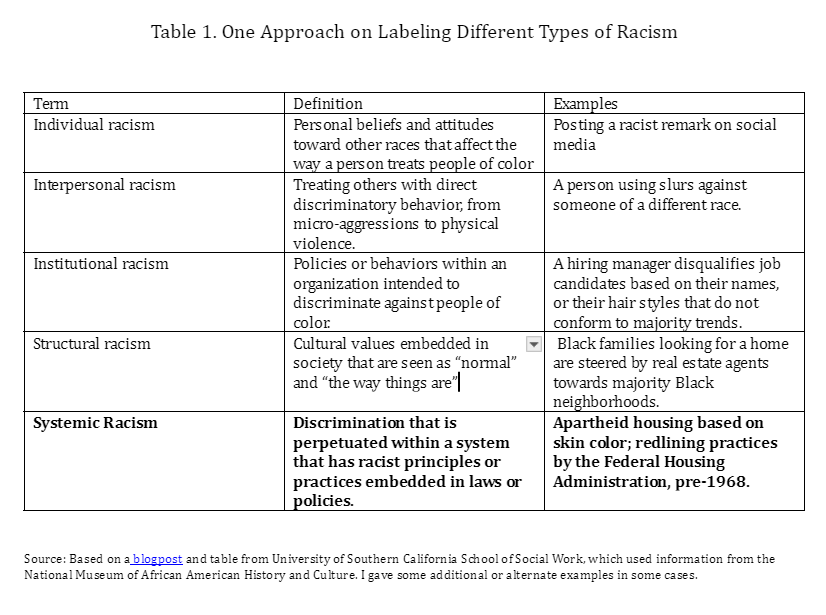

These definitions are a lot to take in. They are so broad that almost every action in life could be examined through these lenses, yet it would be hard to say where racism begins and ends. As an alternative approach, Table 1 divides racism into different buckets, some of which are easier to measure than others. It is based on information from the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) and University of Southern California’s School of Social Work. Note that systemic racism by these scholars has a much narrower focus than Massey & Denton or Braveman et. al.’s all-encompassing definitions.

In this definition by NMAAHC, systemic racism is buttressed by

systems that are founded on racist principles or practices, such as a

legal framework that creates different opportunities to obtain resources. The most egregious example of systemic racism in housing was the South African

apartheid system, a formal legal system that existed from 1948-1994. Whites could own land with titled deeds, whereas Blacks were forced to live in crowded settlement areas, with no hope of homeownership. As seen in Table 2, cultural attitudes, informal rules, or personal beliefs can also be racist, but are inherently subjective and typically outside economists’ scope of inquiry. Thus, sociologists and psychologists are better equipped to study these latter aspects of racism than economists.

For the purpose of this article, I define systemic racism as laws, policies and regulations that result in quantifiably different outcomes for different races. As I will later detail, systemic racism can be either explicit or implicit in nature.

Government Policies: Examples of Explicit Systemic Racism in the United States

While free market conservatives may differ on a number of different issues from progressives and liberals, one area of agreement is that government is a powerful system that can create and sustain systemic racism over the long haul. Over the United States’ history, laws and local regulations were put in place that explicitly prevented Black families from acquiring property and financial capital, through locking out access to neighborhoods and mortgage credit. Here are four examples of systemic racism.

1. Racial covenants: locking Blacks out of neighborhoods

Many examples over history prevented Blacks from enjoying the same access to property as Whites. One way was through racial covenants. A racial covenant is a private contract in which property owners within a defined geographic area collectively agree not to rent or sell to Black residents. For example, in 1927, the Chicago Real Estate Board created a way to block the entry of Blacks into White neighborhoods known as a “racial covenant.” The Board offered the model to other cities for adoption throughout the country (Massey & Denton,

1993). Violators could be sued in civil court, after the racial covenant was approved by the locals. Here we see the government as not the instigator, but the enforcer of systemic discrimination, using a racial covenant that works as effectively as a local law.

2. Federal home loans: Squeezing access to mortgage credit

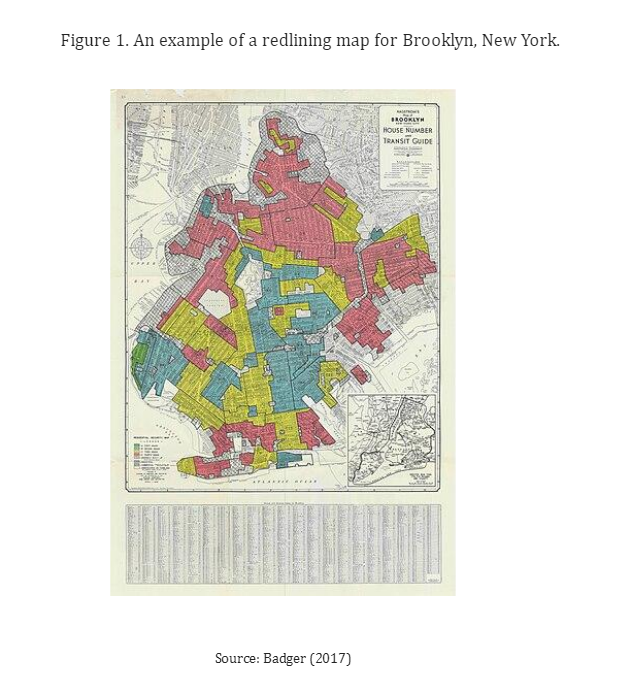

In 1933, the Roosevelt Administration created the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) to help middle class homeowners refinance their mortgages using long-term, federally insured, low-interest loans. HOLC created maps with color-coded neighborhoods according to their perceived creditworthiness. Green was safe, yellow was caution, and red was excessive risk, or what became known as “redlining.” Black city residents almost always lived in the red zones.

The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) insured these loans. It sponsored redlining policies between 1934 to the late 1960s, with an FHA Underwriting Manual that concluded that “no loan could be economically sound if the property was located in a (red-lined) neighborhood that was or could become populated by Black people, as property values might decline over the life of the 15- to 20-year loans they were attempting to standardize. The FHA emphasized the negative impact of "infiltration of inharmonious racial groups" on credit risk (

Federal Reserve, 2023). This made it nearly impossible for Black residents to obtain a mortgage (Rothstein,

2017).

Without access to mortgage credit, even if Blacks owned their homes, they could not tap into their home equity to qualify for federally insured second mortgages in order to make home repairs or improvements (Dickerson, 2021), something White households could do to maintain or increase household wealth over time.

3. The G.I. Bill

After World War II, the federal government arranged for a parallel mortgage loan program for veterans through the G.I. bill, which by itself did not exclude Black soldiers. However, the mortgage loans needed the guarantee of the FHA and as a result, the vast majority of Black veterans could not get loans in majority Black neighborhoods where most lived. For example, in New York and northern New Jersey, out of 67,000 mortgages insured by the G.I. Bill, fewer than 100 of those were issued to non-Whites

(Katznelson 2006; Blakemore, 2023).

4. Urban renewal projects

In the 1960s, hundreds of cities engaged in federally funded highway projects, which were optimistically called “urban renewal.” With these projects, cities sought the path of least resistance and the lowest opportunity cost in terms of lost tax revenue. Unfortunately, the renewal reinforced previous housing policies, largely sparing wealthier, Whiter residents, whereas Black neighborhoods were often demolished. They were the least valued in both an economic and political sense, having lower property values and little political power to oppose the change. Relatively class-diverse Black neighborhoods and thriving business districts were replaced with decaying neighborhoods with no way to plug into a once thriving economic network (Richardson 2023b).

How New Housing Laws Created Implicit Systemic Racism: two examples

Over time, the federal government transformed overtly racist regulations into self-described “remedies” for the past regulations. The 1968 Fair Housing Act prohibited discrimination in the housing market based on race, religion, national origin and sex (

HUD, n.d.).

Compelling evidence indicates the failure of these new government policies to reverse long-standing trends. Decades later, Black households have the lowest homeownership rate nationally—30.0 percentage points lower than White households, at just 44.7 percent. This gap has held for more than 50 years and in recent years has even widened, as seen in Figure 2 below.

The new form of implicit systemic racism contains policies that are not overtly or deliberately racist in their language, in contrast to the pre-1968 federal housing policies. It operates through apparently neutral legal mechanisms that act in a much more invisible way to sustain historical differences in Black and White household ownership patterns. I examine two of them, zoning regulations and the 2008 Dodd-Frank Banking Act.

1. Maintaining “neighborhood character” through zoning

Although tax, lending, and land use laws do not explicitly discriminate against nonwhites, many of these laws continue to favor the status quo, made up of homeowners who are disproportionately White and higher income. In this sense, they can be characterized as a form of implicit systemic racism. For example, current zoning laws and policies seek to preserve the “character” of neighborhoods in order to perpetuate the status quo of neighborhoods that are segregated by race and by income. These zoning laws either ban or make it cost prohibitive for developers to build affordable and multi-family housing in higher-income and predominantly White neighborhoods.

These laws stem from homeowners’ strong feelings that increased density will decrease their property values and wealth. Understandably, homeowners don’t have to be racist to want to preserve their wealth, but the zoning laws still end up isolating one racial group from another, since Black families typically have far less ability to purchase a home. That leads to pockets of poverty on one hand, and growing wealth and property values on the other in many cities across the United States. In this sense, these regulations are not overtly racist but they lead to outcomes that do not give those in the lower tier of income the same opportunity to move up the economic ladder.

2. The 2010 Dodd-Frank Banking Act (DFA) Worsen Lending to Minorities

The DFA, in its effort to discipline the large Wall Street banks after the Great Recession of 2008-10, made it more expensive to be in the banking business in general. It required an extensive and intensive income verification process, and lenders were forced to provide special training to all loan officers. Ironically, the largest Wall Street banks were able to shoulder these increased costs far more easily than smaller banks. Community banks, which are most likely to lend to Black communities, were hit particularly hard by these rising fixed costs, since they issued a larger share of small dollar mortgages and had less financial capital to absorb these blows. These regulatory changes were imposed without regard to the social capital and local knowledge possessed by community banks for their customers. Thousands of smaller banks have either merged with larger banks or gone out of business, making it far more difficult for Black households to obtain mortgages (Richardson, 2023a).

Besides raising overhead costs across the banking system, the DFA capped the fees and points that lenders can charge for processing a loan on a sliding scale, based on the size of a loan. The caps were meant to prevent “exploitative behavior” on the part of the banks for charging “unfair” or “greedy” prices for executing loans and were meant to protect low-income families. However, the caps also created a disincentive for banks to originate small loans since they were even more unprofitable. This disproportionately hurts Black families more because they are more likely to seek smaller loans, given their smaller wealth position on average (Richardson, 2023a).

Conclusion

Even after the abolishment of slavery in 1865, the United States’ government systematically excluded Black families from building wealth up until 1968. It did so through laws and policies that specifically made it difficult or impossible to purchase property. That history of explicit systemic racism, thankfully, is behind us. However, persistent differences in the Black-White Homeownership gap suggest that much work needs to be done. Cities need less restrictive zoning to allow easier entry into homeownership and in addition, the Dodd-Frank Act needs modification to reduce overhead costs for smaller banks, which have traditionally offered more mortgages to communities of color. Until that is changed, long-standing wealth gaps will exhibit the qualities of implicit systemic racism, even if the policies themselves are not explicitly directed to achieve racist goals.

References

Blakemore, Erin (2023). “How the GI bill’s promise was denied to a million Black WWII Veterans.” History.com, June 21.

Braveman, Paula, Elain Arkin, Dwayne Proctor, Tina Kauh and Nicole Holm (2022). “Systemic and structural racism: definitions, examples, health damages, and approaches to dismantling.” Health Affairs 41(2). Feb. 2022.

Cortright, Joe and Dillon Mahmudi, “Lost in place: why the persistence and spread of concentrated poverty- not gentrification- is our biggest urban challenge,” City Observatory, December 2014.

Dickerson, A. Mechele (2021). “Systemic Racism and Housing.” Emory Law Journal. 70 (7), pp. 1535-1576.

Federal Reserve (2023). “Redlining.” Online article, June 2.

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). “History of fair housing.” Online article, n.d.

Katznelson, I. (2006). When affirmative action was white: An untold history of racial inequality in twentieth-century America. W. W. Norton.

Massey, D. S., & Denton, N. A. (1993). American apartheid: Segregation and the making of the underclass. Harvard University Press.

Badger, Emily (2017). “How redlining’ racist effects lasted for decades.” New York Times, August 24th.

Richardson, Craig and Zach Blizard (2023a). “Did the 2010 Dodd-Frank Banking Act deflate property values in low-income neighborhoods? Public Choice, 197(3), pp. 433-454.

Richardson, Craig and John Railey (2023b). “A transitional gains trap: How city backed transportation monopolies in the early twentieth century damaged economic mobility for the next one hundred years.” Journal of Private Enterprise 38(3), pp. 25-45.

Rothstein, R. (2017). The color of law: A forgotten history of how our government segregated America. Liveright Publishing: New York.

In 2019, Black people made up 12.2% of the U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey). Blacks, however, represent 26.6% of total arrests, including 51.2% of murder arrests, 52.7% of robbery arrests, 28.8% of burglary arrests, 28.6% of motor vehicle theft arrests, 42.2% of prostitution arrests, and 26.1% of drug arrests (FBI’s Uniform Crime Report, Table 43).

In 2019, Black people made up 12.2% of the U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey). Blacks, however, represent 26.6% of total arrests, including 51.2% of murder arrests, 52.7% of robbery arrests, 28.8% of burglary arrests, 28.6% of motor vehicle theft arrests, 42.2% of prostitution arrests, and 26.1% of drug arrests (FBI’s Uniform Crime Report, Table 43).