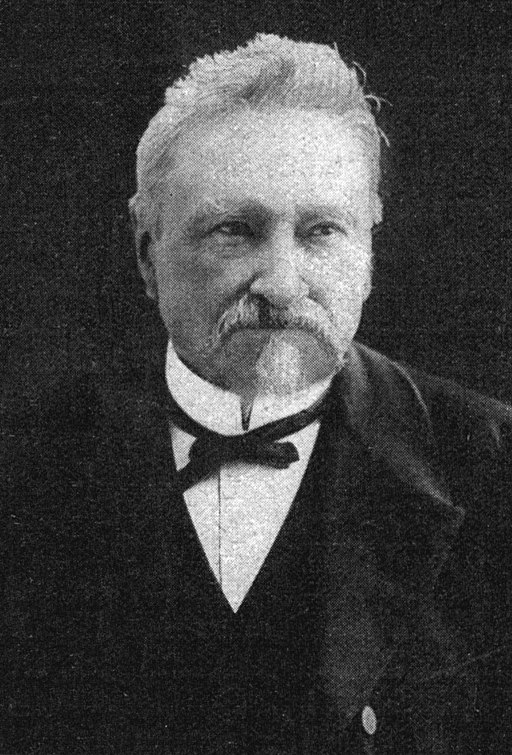

Gustave de Who?

Gustave de Who?

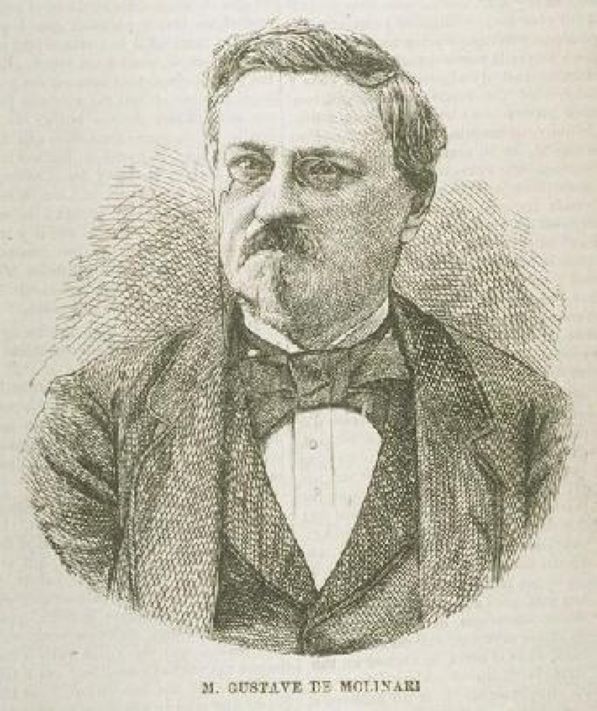

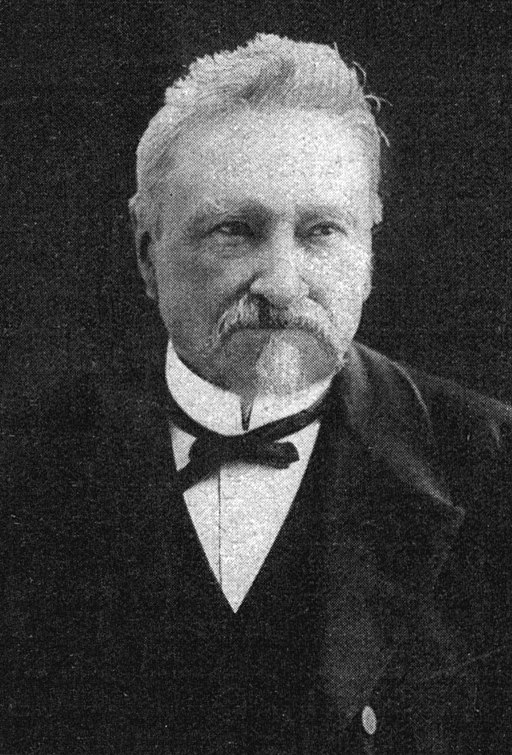

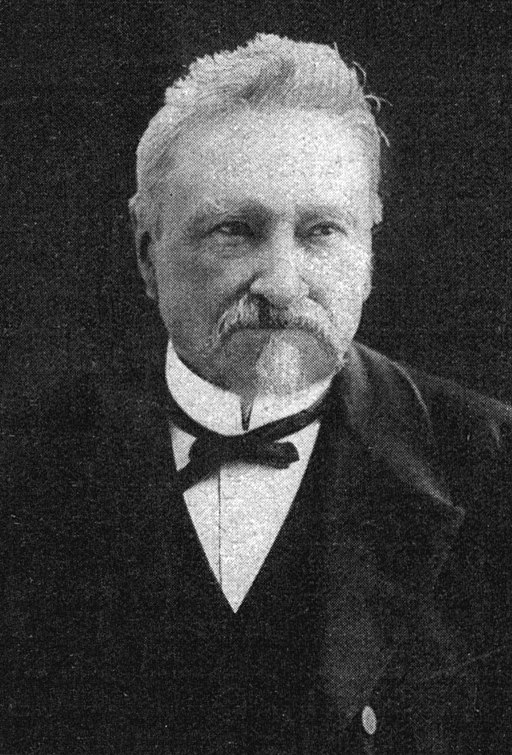

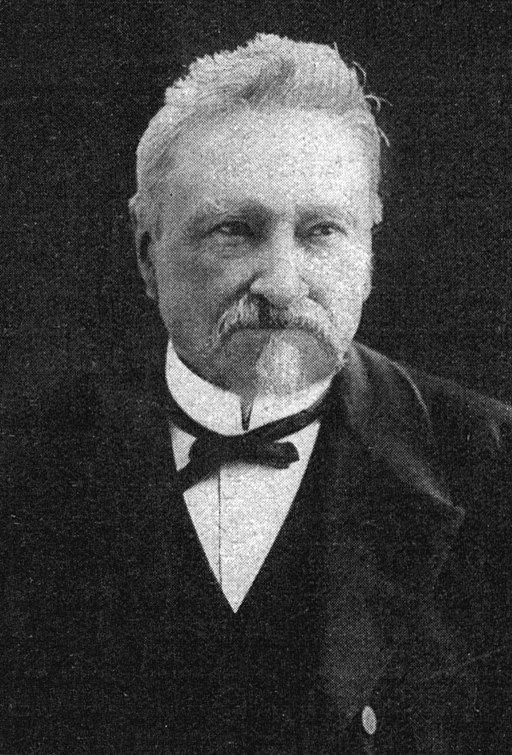

Today the Belgian-born economist

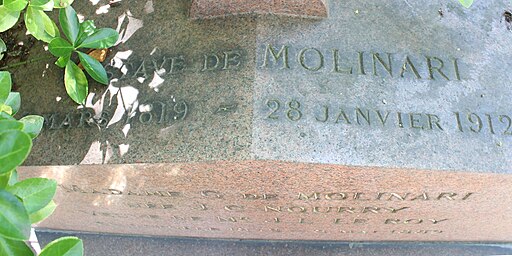

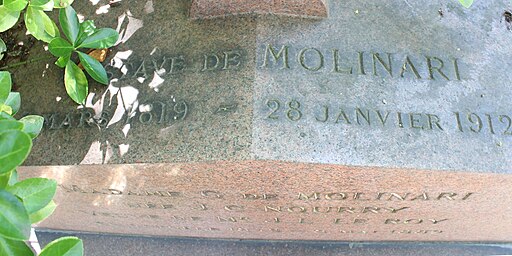

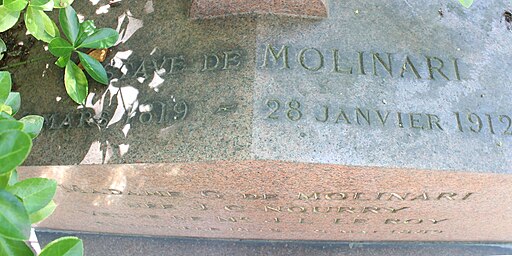

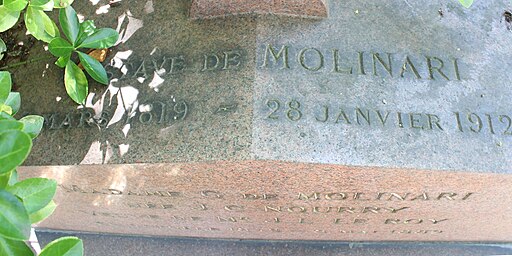

Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912) is little known outside of libertarian circles, and most of his work remains untranslated. Molinari’s fame was once much greater; in his own day his works were discussed by such internationally prominent intellectual figures as

Lord Acton, Henry James,

Karl Marx,

Thorstein Veblen, and

Frédéric Passy (first recipient, with Jean Henry Dunant, of the Nobel Peace Prize), and he was an important influence on Vilfredo Pareto.

Born in Liège, Molinari made his way to Paris at around age 21 and fell in with the classical liberal movement centered on the Société d’Économie Politique and working in the tradition of

Jean-Baptiste Say;

Frédéric Bastiat in particular became an important colleague and mentor. Writing in a clear, engaging, and witty style modeled on Bastiat’s, Molinari penned dozens of works in economics, sociology, and political theory and advocacy, on topics ranging from the economic analysis of history to the future of warfare and the role of religion in society, as well as memoirs of his travels in Russia, North America, and elsewhere; his contemporaries described him as “the law of supply and demand made into man.” He eventually served as editor of the prestigious

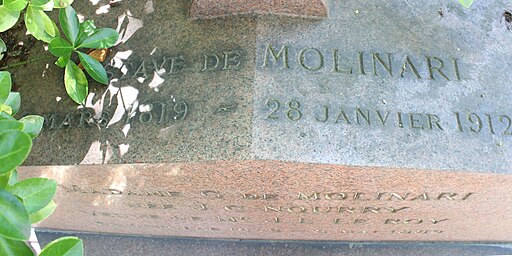

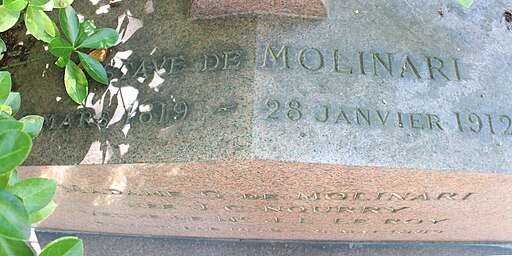

Journal des Économistes, chief organ of French liberalism, from 1881 to 1909. He is buried in Père Lachaise cemetery, in a grave adjoining that of fellow radical liberal

Benjamin Constant.

But Molinari’s chief claim to fame today, among those who have heard of him at all, is his status as the first thinker to describe (most notably in his article “The Production of Security” and book

Les Soirées on the Rue Saint-Lazare, both published in 1849) how the traditional “governmental” functions of security could be provided by market mechanisms rather than by a monopoly state – the “free-market anarchist” position later developed and popularized by such thinkers as

Lysander Spooner, Benjamin Tucker, John Henry Mackay, and Francis Dashwood Tandy in the nineteenth century, and Murray Rothbard, David Friedman, Bruce Benson, and Randy Barnett in the twentieth.

[1] The Road to Market Anarchism

To understand the importance of Molinari’s contribution, some historical context is useful. The extent of the state’s proper sphere had long been a vexed question among classical liberals. That it should be small, most agreed; but how small? Even if liberals were generally more optimistic concerning the prospects for peaceful cooperation in a stateless social order than

Thomas Hobbes had been in his 1651

Leviathan, they still tended, along the lines laid out in

John Locke’s

Second Treatise of Government, to regard a governmental monopoly – albeit a sharply limited one – as an essential bulwark of liberty.

One of the first liberal thinkers to question this consensus was

Thomas Paine. In his 1776

Common Sense, Paine had described government as a “necessary evil”; but sixteen years later – probably under the influence of the spontaneous-order analyses of thinkers like Adam Smith, whose work Paine praises – he seems to have become less certain of the “necessary” part. In

The Rights of Man,

Paine writes:

Great part of that order which reigns among mankind is not the effect of government. It has its origin in the principles of society and the natural constitution of man. It existed prior to government, and would exist if the formality of government was abolished. The mutual dependence and reciprocal interest which man has upon man, and all the parts of civilized community upon each other, create that great chain of connection which holds it together. The landholder, the farmer, the manufacturer, the merchant, the tradesman, and every occupation, prospers by the aid which each receives from the other, and from the whole. Common interest regulates their concerns, and forms their law; and the laws which common usage ordains, have a greater influence than the laws of government. In fine, society performs for itself almost everything which is ascribed to government. ... It is to the great and fundamental principles of society and civilization – to the common usage universally consented to, and mutually and reciprocally maintained – to the unceasing circulation of interest, which, passing through its million channels, invigorates the whole mass of civilized man – it is to these things, infinitely more than to anything which even the best instituted government can perform, that the safety and prosperity of the individual and of the whole depends.

Moreover, unlike the primitivist, propertyless anarchist utopia that

Jean-Jacques Rousseau had envisioned in his

Discourse on the Origin of Inequality, the stateless society that Paine envisioned was clearly a commercial society where order was maintained by industry, trade, and economic self-interest.

Paine did not himself draw from his analysis the moral that

all state functions should be turned over to private enterprise; but he opened the door to such a conclusion, and other thinkers would soon be walking through it.

William Godwin explicitly credited this passage from Paine with inspiring his own anarchist manifesto the following year, and other market-friendly advocates of a stateless society soon followed, including

Thomas Hodgskin in England, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon in France, Johann Gottlieb Fichte in Germany, and Josiah Warren and Stephen Pearl Andrews in the United States.

[2] Within Molinari’s own French liberal tradition, such pioneers as

Jean-Baptiste Say, Charles Dunoyer, and

Augustin Thierry had flirted, at least for a time, with the notion of a stateless society as a potentially viable ideal.

But while these thinkers tended to speak of turning governmental services over to the realm of economic enterprise rather than to that of political compulsion, they offered no real details as to how such functions as security might be provided in the absence of the state. And here we see the significance of Molinari’s contribution. Molinari’s account may not have been as sophisticated as those of some of his successors; he may not have addressed all the objections with which those successors have had to grapple; and he may have said disappointingly little about the market provision of

legal norms, a topic that looms large in more recent market anarchist thought. But Molinari was the first thinker to identify and describe the

economic mechanisms by which the nonstate provision of security might be effected; and this arguably entitles him – despite his not using the term “anarchist” himself

[3] – to be considered the originator of market anarchism.

The Competitive Provision of Security

Molinari’s approach to the topic of security provision involves treating the state as a firm, whose managers are subject to the same economic incentives as those of other firms; in this respect he may be seen as a pioneer of public choice analysis. Molinari points out that there are three ways in which any good or service, security included, may be provided. First, the market for the good or service may be compulsorily restricted to a single provider or privileged group of providers; this is monopoly, which in the case of security corresponds to monarchy, wherein the royal family in effect owns the entire security industry. Second, the market may be managed by or on behalf of society as a whole; this is communism or collectivization, which in the case of security corresponds to democracy, wherein the security industry is in effect publicly owned. Third, the market may be thrown open to free competition, or laissez-faire, a situation which in the case of security Molinari calls freedom of government, and which his successors would call anarchy.

Now in the case of goods and services other than security, the incentival and informational perversities that beset both monopolistic and collective provision are well known, as is the superiority of free competition in respect of both efficiency and inherent justice; why, Molinari asks, should security be treated any differently? On the contrary, Molinari argues, the absence of market competition is even

more dangerous in the field of security than elsewhere, since it not only serves as the enabling cause of monopolies in other fields, but also leads to warfare – both externally, as states strive to extend their territory, and internally, as interest groups struggle to direct the state’s energies to their own purposes.

[4] France’s own recent experience with democracy, in the wake of the 1848 revolution, played a role in weakening liberal enthusiasm for democracy generally; that Molinari’s proposal comes the immediately following year is probably no coincidence. But unlike some of his liberal colleagues (including Dunoyer), Molinari did not look to a restoration of monarchy, either Bourbon or Orleanist (let alone Bonapartist), as an attractive solution to democracy’s failings, instead upholding market anarchism as an alternative to autocratic and collective rule alike.

In place of the state provision of security, then, Molinari proposes a system of competing security firms on the model of insurance companies, with clients free to switch providers without switching locations; the need to retain clients, he argues, would keep prices low and services efficient.

[5] In terms reminiscent of Proudhon’s call for “the dissolution of the state in the economic organism,” Molinari explains that he calls for neither “the absorption of society by the state, as the communists and collectivists suppose,” nor “the suppression of the state, as the [non-market] anarchists and nihilists dream,” but instead for “the diffusion of the state within society.”

[6]

"The present admirable constitution of the courts of justice in England was, perhaps, originally in a great measure, formed by this emulation, which antiently took place between their respective judges"

Inasmuch as Molinari was unfamiliar with the recent research on historical examples of stateless or quasi-stateless legal systems to which more recent proponents of market anarchism are able to appeal, his arguments are necessarily more theoretical than historical; but he does cite

Adam Smith’s argument that the “

present admirable constitution of the law courts in England” is due to “that emulation which animated these various judges, each striving competitively....” And when military defense is needed, Molinari maintains, security firms would find it in their interest to pool resources to fend off the invader; as for military offense, firms would find it difficult to engage in this without a captive tax base.

“One day,” Molinari predicted in 1849, “societies will be established to agitate for the freedom of government, as they have already been established on behalf of the freedom of commerce.” His words have proven prophetic. Molinari’s personal fame may have fallen over the course of the past century, but the popularity of his most distinctive idea has had the opposite trajectory, as today’s profusion of market anarchist websites attests. Molinari, by contrast, stood virtually alone; his classical liberal colleagues, even those like Dunoyer who had veered close to anarchism in their own writings, were largely unconvinced by his arguments, objecting that competition presupposes, and so cannot provide, a stable framework of property rights, and that competition in security was a recipe for civil war.

[7] Molinari himself came, in later writings, to moderate his own position in the face of public-goods objections, arguing that pure competition was appropriate only for goods and services of “naturally individual consumption,” while for those of “naturally collective consumption” the only role for competition was in bidding for government contracts.

[8] Replies to these sorts of objections are easy to come by nowadays, but were not so in Molinari’s own day and milieu.

[9] It is unclear how much influence, if any, Molinari’s proposal for competing security firms had. Similar ideas would later be popular in Benjamin Tucker’s circle, but may have been developed independently – though Tucker did read widely in French, and Molinari was hailed (albeit at a fairly late date) as an anarchist in the pages of Tucker’s journal.

[10] Some passages in Anselme Bellegarrigue’s 1850

Anarchy: A Journal of Order and Proudhon’s 1851

General Idea of the Revolution show possible traces of the influence of Molinari’s 1849 arguments as well. Another thinker likely

[11] influenced by Molinari was a fellow Belgian, Paul Emile de Puydt, whose 1860 article “Panarchy” called for competing systems of government within the same geographical territory, though unlike Molinari he seems to have envisioned a single provider for the different systems.

[12] But Molinari’s status as originator of market anarchism is more chronological than causal.

The Organization of Labor

The other contribution that most clearly differentiates Molinari from his liberal colleagues is his proposal for a system of labor-exchanges.

Concerns about unequal bargaining power between labor and capital are often regarded as a concern exclusive to the anti-market left; but Molinari, to his credit, recognizes the problem and seeks to address it. Molinari quotes favorably Adam Smith’s observation that there is “everywhere a tacit but perpetual conspiracy among the employers, to stop the present price of labor from rising,” and that with “employers being fewer in number, it is much easier for them to collude,” and “the employers can hold out very much longer.” But Molinari’s diagnosis of the problem is the partial insulation of employers from market discipline. Such insulation, Molinari holds, is partly the result of laws favoring employers over laborers, and thus can be addressed in part by repealing such laws; Molinari, like Bastiat, is a stern critic of anti-union legislation.

[13] But apart from such laws, he tells us, labor is also hampered by its lack of mobility in comparison with capital. Happily, modern transportation technology makes it possible for workers to relocate swiftly from low-wage to high-wage areas; Molinari’s solution, then, is to create a private network of labor-exchanges whereby employers could bid on the services of workers near and far. Labor unions and mutual credit societies would “provide their collective guarantee to enterprises of transportation and job placement” and thus secure “to the mutualized laborers the funds necessary to pay the cost of transporting them to the most advantageous market.”

[14]

The idea is an ingenious one, but it is reasonable to worry that Molinari has exaggerated the extent to which labor’s mobility can be increased. The economist H. C. Emery plausibly attributes labor’s comparative immobility “not so much to the lack of adequate machinery of exchange or to ignorance of the foreign (non-local) demand” as to the fact that a “laborer is after all a man” who “has a wife and children, and desires a fixed habitat for them,” and consequently “refuses to have his household moved hither and thither at every fluctuation of demand.”

[15] Admittedly, telephone and internet have since made instant mobility a reality for those tasks that can be done via telecommuting, but there are still many jobs that require a physical presence.

Moreover, unlike many of his liberal and libertarian contemporaries such as

John Stuart Mill,

Herbert Spencer, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon,

Lysander Spooner, Benjamin Tucker, and to a certain degree

Wordsworth Donisthorpe, Molinari never questioned the necessity of the wage system itself,

i.e., the separation of labor from ownership. Obviously one solution to unequal bargaining power between capital and labor would be worker control of industry – not in the collectivized version favored by state socialists, but in the form of individual workers’ cooperatives and independent contractorships competing on a free market. Eliminating legal barriers to worker control would force traditional hierarchical firms, unlovely in their work environments and blinded by the informational chaos that hierarchy brings, to compete on a level playing field with worker-controlled ones, to the likely advantage of the latter. Molinari never seriously addresses this pro-market but anti-capitalist alternative; his references to Proudhon, for example, are invariably dismissive, lumping him in with communists and state socialists, with little apparent recognition of his pro-market views.

[16]

Molinari’s Hits and Misses

But while labor-exchanges and market anarchism – both schemes for weakening the power of elites by extending the range of competition – may be Molinari’s two most distinctive contributions, he is a fascinating, wide-ranging thinker whose ideas on a variety of topics deserve study and consideration, both for their strengths and for their potential weaknesses.

In his moral foundations Molinari combines consequentialist and deontological considerations. This seems like a good idea: purely consequentialist approaches to liberty tend to compromise moral principle and undervalue human dignity, while purely deontological approaches tend to make the normative force of moral principles mysterious, while leaving the beneficial consequences of liberty a fantastic coincidence. But Molinari never makes clear exactly how the consequentialist and deontological dimensions of ethics are supposed to be related.

Molinari also describes private property as an extension of the self, a defensible neo-Lockean position, yet fails to explain how such a conception is compatible with his support for “intellectual property” laws. How can ideas, inventions, and artistic compositions still be an extension of their creators when the objects in which they are realized are the minds, bodies, and property of other people?

Molinari’s analyses are often marred, moreover, by narrowly egoistic and hedonistic assumptions about human psychology that a couple of simple thought-experiments should easily dispel.

[17] And while remaining coy about his own religious commitments if any, he holds that for the masses, at least, a commitment to justice will be unstable without the motivations provided by religion. This seems hard to believe; the percentage of religious believers is high in Poland and low in the Czech Republic, for example, yet we do not see the kind of divergence between the two countries that Molinari would predict.

Molinari’s historical accounts of the evolution of social institutions are fascinating, and bear signs of Spencer’s influence; but unlike Spencer, Molinari offers virtually no evidence for them, and it is often unclear whether these are supposed to be literally accurate narratives or hypothetical constructs. The accounts also arguably suffer from excessive economic imperialism; have we really accounted for the spread of Christianity in Europe by noting that “Paganism was an expensive religion, Christianity a cheap one”?

[18] Molinari’s opposition to warfare and militarism is also commendable (his very name is cosmopolitan, combining three languages in one); yet his proposed remedy – international arrangements for collective security – seems problematic. Would such arrangements indeed make war less likely, by deterring aggression, or might they instead pose a risk of

extending warfare by drawing allies in, while simultaneously threatening the political decentralization that he favors? And his contention that warfare and the state were necessary and justified in early historical periods – a historicist thesis widely shared by radicals in his day

[19] – also seems inconsistent with his emphasis on the absolute, timeless, and immutable character of economic and moral principles.

Perhaps the least appealing of Molinari’s positions (unfortunately not an unusual one in his era, but again in seeming tension with his aforementioned absolutism) is his view that the vast majority of the human race – including women, nonwhite races, and a large percentage of the working class – are not yet ready for the liberty he advocates, and need to submit to a condition of at least temporary “tutelage,” while waiting for scientists to improve the human race through (admittedly voluntary) programs of “viriculture” (i.e., eugenics).

Nothing to Gain But Their Chains

Yet for all his shortcomings, Molinari remains not only an interesting historical thinker, but also a vital lodestar for the liberty movement today. He understood that the solution to abuse of power is not to elect better people into power, or to persuade current holders of power to play nice, or to rein them in with paper constitutions whose interpretation the powerful themselves will ultimately control, but rather to dissolve that power by extending the range of competitive markets.

All over the world, ordinary people long to be free of the tyranny of bosses and rulers; Molinari’s labor-exchange proposal, however flawed, plausibly identifies lack of competition as the linchpin of employer privilege and abuse, while his market anarchism, however incomplete, likewise plausibly identifies lack of competition as the linchpin of state privilege and abuse. Both proposals embody the same essential insight: the way to break the power of plutocrats and statocrats

[20] alike is to subject both to the rule ofcompetition – the adamantine chains of

laissez-faire.

Endnotes

[1] This position has also been described both as “voluntary socialism” and as “anarcho-capitalism,” largely according to which relations between labor and capital its various proponents have thought would or should emerge in a market entirely freed from state interference. More on this below.

[2] The interpretation of Godwin and Proudhon as market-friendly thinkers may be more controversial than in the case of the other theorists mentioned, but is defensible. Godwin held that property should be shared rather than held privately – but also that this should be a free moral choice, and that all forcible interference with private property and trade should be rejected. Proudhon (to simplify a rather complex story) attacked a form of private ownership he called “property,” but defended another form of private ownership he called “possession”; hence he was by no means an enemy of private ownership as such.

[3] As few early anarchists did in any case; the term was originally associated specifically with the Proudhonian tradition.

[4] Here Molinari is drawing on the liberal theory of class conflict developed by such predecessors as Dunoyer, Thierry, and Charles Comte.

[5] For criticism of the assumption that market provision of security must always take the form of competing for-profit firms, see Philip E. Jacobson, “Three Voluntary Economies,”

Formulations 2, no. 4 (Summer 1995); also available at <

http://www.freenation.org/a/f24j1.html>.

[6] Molinari,

L’Évolution Politique et la Révolution (1888), pp. 393-94.

[7] For French liberal reaction to Molinari’s proposals, see “Question des limites de l’action de l’État et de l’action individuelle débattue à la Société d’économie politique” (

Journal des Économistes, t. 24, no. 103 [15 Oct. 1849], pp. 314-316), also available at <

https://praxeology.net/JDE-LSA.htm>, and Charles Coquelin’s review of

Les Soirées de la Rue Saint-Lazare (

Journal des Économistes, t. 24, no. 104 [15 Nov. 1849], pp. 364-372, also available at <

https://praxeology.net/CC-GM-RSL.htm> . De Puydt’s “Panarchy” (see above) may possibly have been motivated by just these criticisms, as a way of retaining as much Molinarian competition as possible within a monopoly framework.

[8] Molinari,

Esquisse de l’organisation politique et économique de la Société future, 1899.

[9] For contemporary discussion pro and con concerning such objections to market anarchism, see Edward P. Stringham, ed.,

Anarchy and the Law: The Political Economy of Choice (Transaction, 2007) and

Anarchy, State and Public Choice (Edward Elgar, 2005); Roderick T. Long and Tibor R. Machan, eds.,

Anarchism/Minarchism: Is a Government Part of a Free Country? (Ashgate 2008); and on the broader question of public goods, Tyler Cowen, ed.,

Public Goods and Market Failures: A Critical Examination (Transaction, 1992).

[10] S. R. [possibly S. H Randall], “An Economist on the Future Society,”

Liberty 14, no. 23, whole number 385 (September 1904), p. 2.

[11] Two Belgian economists independently defending competing-government schemes within a single eleven-year-old period would at any rate be a surprising coincidence, especially when the more prominent of the two is the one who wrote first.

[12] De Puydt, “Panarchie,”

Revue Trimestrielle (July 1860); also available at <

http://www.panarchy.org/depuydt/1860.eng.html> . Curiously, de Puydt explicitly lists “the an-archy of M. Proudhon” as one of the options to be made available to the provider’s clients; how a monopolistic firm is to offer absence of monopoly as one of its possible services is unclear.

[13] For Bastiat’s defense of unions see “Speech on the Suppression of Industrial Combinations,” available at <

https://www.econlib.org/library/Bastiat/basEss11.html>.

[14] Molinari,

Les Bourses du Travail (1893), ch. 8.

[15] Henry Crosby Emery, review of

Les Bourses du Travail, in

Political Science Quarterly 9, no. 2 (June 1894), pp. 306-308; also available at <

https://praxeology.net/HCE-GM-LE.htm>.

[16] An article – simultaneously sympathetic and condescending in tone – on the free-market anticapitalist position of Benjamin Tucker and his circle did appear in the

Journal des Économistes under Molinari’s editorship; see Sophie Raffalovich, “Les Anarchistes de Boston,”

Journal des Économistes 41, 4th series (15 March 1888), pp. 375–88. For Tucker’s reply, see Benjamin R. Tucker, “A French View of Boston Anarchists,”

Liberty 6 (4), whole no. 134 (29 September 1888), p. 4. For more recent defenses of an anticapitalist version of free-market anarchism, see Gary Chartier and Charles W. Johnson, eds.,

Markets Not Capitalism: Individualist Anarchism Against Bosses, Inequality, Corporate Power, and Structural Poverty (Minor Compositions, 2011), also available at <

http://radgeek.com/gt/2011/10/Markets-Not-Capitalism-2011-Chartier-and-Johnson.pdf> ; Kevin A. Carson, 2007,

Studies in Mutualist Political Economy, (BookSurge, 2007), also available at <

http://www.mutualist.org/sitebuildercontent/sitebuilderfiles/MPE.pdf>, and

Organization Theory: A Libertarian Perspective (BookSurge, 2008), also available at <

http://www.mutualist.org/sitebuildercontent/sitebuilderfiles/otkc11.pdf>; Gary Chartier,

Anarchy and Legal Order: Law and Politics for a Stateless Society (Cambridge, 2013); and Samuel Edward Konkin III,

New Libertarian Manifesto (Koman, 1983), also available at: <

http://agorism.info/NewLibertarianManifesto.pdf>.

[17] See Christopher Grau, “Matrix Philosophy: The Value of Reality. Cypher and the Experience Machine,” available at <

http://www.dvara.net/hk/matrixessay3.asp>.

[18] Molinari,

Religion (1892), I.6.

[19] For example, Proudhon, Spencer, and Marx all agree on this as well – though Bastiat, interestingly, does not.

[20] I owe the term “statocrat” to Bertrand de Jouvenel,

On Power: The Natural History of Its Growth, trans J. F. Huntington (Liberty Fund, 1993), p. 174n.

ADDITIONAL READING

Online Resources

Works by Molinari at the OLL website: <

/people/136>.

Works on School of Thought: 19th Century French Liberalism <

/collections/28>

A virtual anthology of Molinari's writings on the state between 1846 and 1912 can be found on David Hart's website <

http://davidmhart.com/liberty/FrenchClassicalLiberals/Molinari/anarcho-capitalism.html>.

Works by Molinari mentioned in the Discussion

Readings for Liberty Fund Colloquium, “Gustave de Molinari: The Economics, Ethics, and Evolution of a Free Society” (November 29 - December 2, 2012).

Molinari, Gustave de,

Soirees on the Rue Sant-Lazare. Edited and with an Introduction by David M. Hart. Translated by Dennis O’Keeffe (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, Inc., forthcoming). Draft Chapters 1, 3, 6, 11 are online at the OLL and were used in the LF conference on Molinari. <

Molinari revised chapters 1 3 6 11>. The entire book in draft form can be found here <

Molinari’s Evenings on Saint Lazarus Street 1849>.

The following works by Molinari are listed in chronological order by date of publication:

Gustave de Molinari, Histoire du tarif (Paris: Guillaumin et cie, 1847). Tome 1 Les fers et les houilles. Tome 2 Les céréales.

Daire, E., and G. de Molinari. Melanges d'économie politique. Collection des principaux économistes, t. 14-15. Paris: Chez Guillaumin et ce, 1847.

Gustave de Molinari, "De la production de la sécurité,” Journal des Économistes, 15 February 1849, pp. 277-90.

Gustave de Molinari, Les Soirées de la rue Saint-Lazare; entretiens sur les lois économiques et défense de la propriété. (Guillaumin, 1849).

Coquelin, Charles, and Gilbert-Urbain Guillaumin, eds. Dictionnaire de l’économie politique (Paris: Guillaumin et Cie., 1852-53), 2 vols. Molinari wrote 24 articles and 5 biographies for the DEP.

Gustave de Molinari, Les Révolutions et le despotisme envisagés au point de vue des intérêts matériel. (Brussels: Meline, 1852).

Gustave de Molinari, Cours d'économie politique, professé au Musée royal de l'industrie belge, 2 vols. (Bruxelles: Librairie polytechnique d'Aug. Decq, 1855). 2nd revised and enlarged edition (Bruxelles et Leipzig: A Lacroix, Ve broeckoven; Paris: Guillaumin, 1863). Tome I: La production et la distribution des richesses. Tome II: La circulation et la consommations des richesses.

Gustave de Molinari, Conservations familières sur le commerce des grains. (Paris: Guillaumin, 1855).

Molinari edited and introduced a new edition of Charles Coquelin's book on free banking, Du Crédit et des Banques (1st ed. 1848, 2nd ed. 1859).

Gustave de Molinari, Les Clubs rouges pendant le siège de Paris (Paris: Garnier Frères, 1871).

Gustave de Molinari, Le Mouvement socialiste et les réunions publiques avant la révolution du 4 septembre 1870, suivi de la planification des rapports du capital et du travail (Paris: Garnier Freres, 1872).

Gustave de Molinari, La République tempérée. (Paris: Garnier, 1873).

Gustave de Molinari, L'évolution économique du XIXe siècle: théorie du progrès (Paris: C. Reinwald 1880).

Gustave de Molinari, L'évolution politique et la Révolution (Paris: C. Reinwald, 1884).

Gustave de Molinari, Conversations sur le commerce des grains et la protection de l'agriculture (Nouvelle édition) (Paris: Guillaumin, 1886).

Gustave de Molinari, Les Lois naturelles de l'économie politique (Paris: Guillaumin, 1887).

Gustave de Molinari, Religion. Paris: Guillaumin et Cie, 1892. Translated as Religion, translated from the second (enlarged) edition with the author's sanction by Walter K. Firminger (London: Swan Sonnenschein, 1894).

Gustave de Molinari, Les Bourses du Travail (Paris: Guillaumin, 1893).

Gustave de Molinari, Comment se résoudra la question sociale (Paris: Guillaumin, 1896).

Gustave de Molinari, La viriculture; ralentissement du mouvement de la population, dégénérescence, causes et remèdes (Paris: Guillaumin et cie, 1897).

Gustave de Molinari, Grandeur et decadence de la guerre (Paris: Guillaumin, 1898).

Gustave de Molinari,

Esquisse de l'organisation politique et économique de la Société future (Paris: Guillaumin, 1899). English transaltion:

The Society of Tomorrow: A Forecast of its Political and Economic Organization, ed. Hodgson Pratt and Frederic Passy, trans. P.H. Lee Warner (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904). <

oll2.libertyfund.org/titles/228>.

Gustave de Molinari, "Le XIXe siècle", Journal des Économistes, Janvier 1901, pp. 5-19.

Gustave de Molinari, "Le XXe siècle", Journal des Économistes, Janvier 1902, pp. 5-14.

Gustave de Molinari, Les Problèmes du XXe siècle (Paris: Guillaumin, 1901).

Gustave de Molinari, Questions économiques à l'ordre du jour (Paris: Guillaumin, 1906).

Gustave de Molinari, Économie de l'histoire: Théorie de l'Évolution (Paris: F. Alcan, 1908).

Gustave de Molinari, Ultima Verba: Mon dernier ouvrage (Paris: V. Girard et E. Briere, 1911).

Gustave de Molinari’s proposals to expand the reach of markets deserve our unqualified praise, even if we might be inclined to proceed in ways different from those he suggested. In particular, Molinari’s entrepreneurial attempt to conceive of institutions that might help to better the competitive position of labor in the market reflects his concern with an issue of crucial importance.

Gustave de Molinari’s proposals to expand the reach of markets deserve our unqualified praise, even if we might be inclined to proceed in ways different from those he suggested. In particular, Molinari’s entrepreneurial attempt to conceive of institutions that might help to better the competitive position of labor in the market reflects his concern with an issue of crucial importance.

In

In

Matt Zwolinski offers three arguments in support of Molinari’s pessimism, late in his life, about going all the way to market anarchy. The first is that violence is sometimes a pleasurable consumption activity, the second that individuals are particularly irrational with regard to violence, the third that violence imposes external costs.

Matt Zwolinski offers three arguments in support of Molinari’s pessimism, late in his life, about going all the way to market anarchy. The first is that violence is sometimes a pleasurable consumption activity, the second that individuals are particularly irrational with regard to violence, the third that violence imposes external costs. Thanks to Matt, David F., David H, and Gary for their excellent and thoughtful contributions. Since Gary’s and David H.’s comments leave me nothing to disagree with, and David F.’s with very little – and the only real disagreement with me that David F. raises (about the reasons for the dominance of large hierarchical firms) is already preemptively addressed in Gary’s piece – I’ll focus my remarks on Matt’s response. I don’t feel too guilty about this, since I expect that Gary and the Davids will have plenty to take issue with, both in Matt’s piece and in one another’s.

Thanks to Matt, David F., David H, and Gary for their excellent and thoughtful contributions. Since Gary’s and David H.’s comments leave me nothing to disagree with, and David F.’s with very little – and the only real disagreement with me that David F. raises (about the reasons for the dominance of large hierarchical firms) is already preemptively addressed in Gary’s piece – I’ll focus my remarks on Matt’s response. I don’t feel too guilty about this, since I expect that Gary and the Davids will have plenty to take issue with, both in Matt’s piece and in one another’s. Like Matt Zwolinski, I too was struck by the similarities between Molinari and Spencer because they appeared to jettison their youthful radicalism and embrace a more bitter and pessimistic view of the prospects for liberty as they aged. They were close contemporaries: Spencer (1820-1903) and Molinari (1819-1912) lived into their 80s and 90s. Perhaps that will be the fate of us all if we live that long!

Like Matt Zwolinski, I too was struck by the similarities between Molinari and Spencer because they appeared to jettison their youthful radicalism and embrace a more bitter and pessimistic view of the prospects for liberty as they aged. They were close contemporaries: Spencer (1820-1903) and Molinari (1819-1912) lived into their 80s and 90s. Perhaps that will be the fate of us all if we live that long!

Another important point which Matt raises which I think is worth pursuing further is Hayek’s argument about “true and false individualism” (1945)

Another important point which Matt raises which I think is worth pursuing further is Hayek’s argument about “true and false individualism” (1945) I want to second what David H. has said about Hayek’s distinction between “true” and “false” individualism, and to add a few points.

I want to second what David H. has said about Hayek’s distinction between “true” and “false” individualism, and to add a few points. In my initial response essay I claimed that Molinari’s anarchism was an example of what F. A. Hayek labeled “false individualism.” In their subsequent essays, David Hart and Roderick Long have both taken issue with this characterization.

In my initial response essay I claimed that Molinari’s anarchism was an example of what F. A. Hayek labeled “false individualism.” In their subsequent essays, David Hart and Roderick Long have both taken issue with this characterization.

I’ve argued that Molinari was a likely influence on de Puydt, and a possible influence on Proudhon and Bellegarrigue. But none of these writers adopted Molinari’s specific proposal of competing security firms; de Puydt substituted competing service packages offered by a single monopoly, Bellegarrigue called for a monopoly security agency as well (albeit a voluntary one), and Proudhon’s proposal is too short on details – at least in the texts I’ve read.

I’ve argued that Molinari was a likely influence on de Puydt, and a possible influence on Proudhon and Bellegarrigue. But none of these writers adopted Molinari’s specific proposal of competing security firms; de Puydt substituted competing service packages offered by a single monopoly, Bellegarrigue called for a monopoly security agency as well (albeit a voluntary one), and Proudhon’s proposal is too short on details – at least in the texts I’ve read.

Matt argues that anarchist thought counts as constructivist rationalism, even if it advocates giving free rein to spontaneous order, so long as the arguments for doing so are based on individual reason. For Matt, constructivist rationalism is a way of thinking, regardless of the content of what is thought. And he identifies Spencer’s case for the law of equal freedom, and Molinari's insistence on absolute economic principles, as instances of such rationalism.

Matt argues that anarchist thought counts as constructivist rationalism, even if it advocates giving free rein to spontaneous order, so long as the arguments for doing so are based on individual reason. For Matt, constructivist rationalism is a way of thinking, regardless of the content of what is thought. And he identifies Spencer’s case for the law of equal freedom, and Molinari's insistence on absolute economic principles, as instances of such rationalism.