Liberty Matters

Steven Horwitz’s comment

I want to chime in briefly on the exchange between Viktor and Geoffrey about the importance of the rules of the game, especially with respect to the “voluntariness” of market interactions and our willingness to accept various market outcomes as legitimate. The distinction that Viktor makes between “harms” that come from the playing of the game of catallaxy within the rules (e.g., a loss of income that comes from a shift in market demand and a new pattern of exchanges) versus the harms that come from people violating those rules (e.g., private predation or private actors seeking to expand the reach of the state for their own personal gain) is crucially important. It is one that free-market liberals should indeed be more vocal about, particularly in the context of issues such as income inequality. We need to hammer home the idea that play within the rules is positive sum, because it benefits all players in the long run even if it increases measured inequality, while violations of those rules are negative sum, because any change in the distribution of income they create are the result of some gaining at the expense of others.

Of course for decades the modern state has rewritten the rules of the game in ways that invite this sort of negative-sum rent-seeking behavior. Private actors have adapted by, on various margins, shifting their profit-seeking resource expenditures to more vigorously compete in the political arena for the rents available there – or to protect themselves against such behavior by others. As more and more firms have felt compelled to open Washington offices to rent-seek and/or rent-protect, the amount of negative-sum behavior has expanded. As problematic as this all is, the degree to which governments have used pure discretion to pick winners and alter the outcome of the game has still been reasonably modest. Rather, the entanglement of rent- and profit-seeking has produced a set of rules that has led to suboptimal games being played.

I wonder, though, whether the last few years haven’t changed this in a significant way. Rather than just setting up rules that make for bad games, the modern state seems more like referees in an American football game who us their discretion to decide what yard line the ball should be placed on and what sorts of plays are legitimate. The bailouts and subsidies of the last half-decade are a perfect example of this sort of behavior by the modern state.

We might distinguish three cases corresponding to this evolution.

1) The liberal ideal: Here the state is (at most) a referee, and all would agree on the rules of the game, legitimating all outcomes as voluntary in the way Viktor and Geoffrey have discussed. 2) The rent-seeking society: The state remains (mostly) a referee but the rules are such that not all would agree to them because of the negative-sum outcomes they produce. In this world, not all outcomes are voluntary. 3) The discretionary state: Here we have not only a set of rules that people do not agree on, but we also have a “referee” who sees its role as more intentionally affecting the outcome of the game by using its discretion to help or harm specific players far more systematically than in the rent-seeking society. Not only are the rules themselves unable to command assent, but the arbitrariness of the enforcement of even those rules that would command assent breaks down any sense that outcomes are legitimate.

Perhaps much of the frustration of groups from Occupy Wall Street to the Tea Party over the last few years reflects the movement toward the third scenario. Confidence in both the fairness of the rules and their enforcement has been shattered to such a degree that perhaps few people feel the outcomes in this very entangled political economy are legitimate.

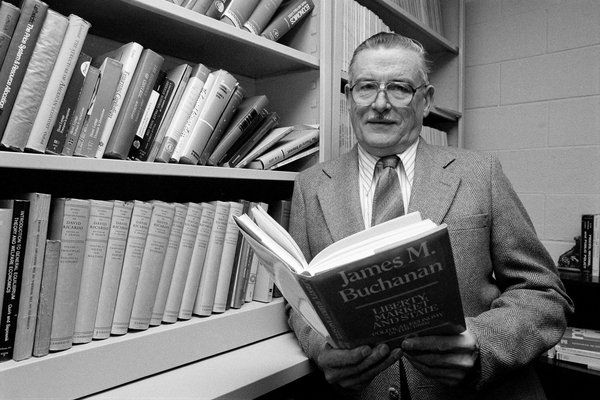

In a world that seems less and less governed by rules, Buchanan’s work couldn’t be more relevant. If indeed western countries have moved to a stage where the state’s power has become increasingly discretionary and has thereby systematically destroyed any remaining belief that economic outcomes are voluntary and therefore legitimate, then not only have we retrogressed to a premodern understanding of the state, but all bets are off as to what happens next. When the referee, and not just the rules, is seen as illegitimate, we are approaching a constitutional crisis (in Buchanan’s sense of constitutional), the outcome of which might not be pretty.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.