Liberty Matters

Henry V: Corrupt beyond the Machiavellian Norm?

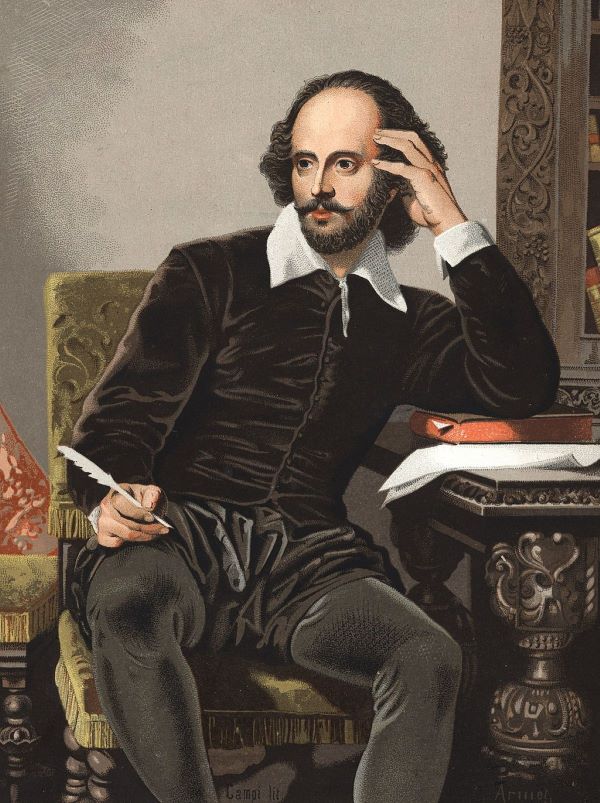

In my final post I will discuss the extent to which Shakespeare's Henry V corrupts himself in the course of his pursuit of conquest over the French. Keeping in view Machiavelli's The Prince and Erasmus's The Education of a Christian Prince, I will argue that Henry corrupts himself by following a Machiavellian strategy to increase his power even as he consciously portrays himself as a devoutly Christian ruler.

Shakespeare's Chorus implicitly draws our attention to Erasmus when it calls Henry "the mirror of all Christian kings" (II.0.6). But early in Henry V, Henry exploits Christianity in ways that justify an unjust war and shifts the blame upon others even as he maintains the appearance of innocence. Speaking to the Archbishop of Canterbury, Henry says,

My learned lord, we pray you to proceed, And justly and religiously unfold Why the law Salique that they have in France Or should, or should not, bar us in our claim. And God forbid, my dear and faithful lord, That you should fashion, wrest, or bow your reading, Or nicely charge your understanding soul With opening titles miscreate, whose right Suits not in native colours with the truth; For God doth know how many now in health Shall drop their blood in approbation Of what your reverence shall incite us to. Therefore take heed how you impawn our person, How you awake the sleeping sword of war: We charge you in the name of God, take heed; For never two such kingdoms did contend Without much fall of blood; whose guiltless drops Are every one a woe, a sore complaint, ’Gainst him whose wrongs give edge unto the swords That make such waste in brief mortality. Under this conjuration speak, my lord, And we will hear, note, and believe in heart, That what you speak is in your conscience wash’d As pure as sin with baptism. (I.i.9-32)

As R. V. Young has noted, Henry's words initially seem in line with Erasmus's deep concerns about war. Erasmus declares that a prince "will never be more hesitant or more circumspect than in starting a war" because "war always brings about the wreck of everything good, and the tide of war overflows with everything the worst."[57] But Young then states that the seeming piety of Henry's speech is undercut by the fact that Shakespeare has already informed readers, through the mouth of Canterbury, that the archbishop has earlier offered Henry an unprecedented donation from the Church should Henry declare war (see I.i.75-81). "Upon inspection," writes Young, Henry's speech "turns out to be a piece of cynical manipulation by which a king who has already made up his mind about what he wants to do pressures corrupt clergymen to furnish a rationalization--indeed take moral responsibility--for a war of doubtful legitimacy."[58] As I noted in "Power and Corruption in Shakespeare's Plays," Canterbury publically absolves Henry's conscience of blame, declaring, "The sin be upon my head, dread sovereign" (I.ii.97).[59] But Canterbury's deflection of blame to himself directly contradicts Erasmus's teaching. Writing about the extreme carnage of war, Erasmus states that a ruler should ask himself, "Shall I alone be the cause of so much woe? … shall all this be laid at my door?"[60] Henry and the Archbishop may employ their rhetorical ruse, but it does not absolve Henry; rather, it implicates Canterbury in Henry's guilt.

As various scholars have noted, Henry's decision to pursue war with France is highly Machiavellian in nature. It goes without saying that Henry follows Machiavelli's advice that a ruler "should seem to be merciful, faithful, humane, religious, and upright" even as he trains himself "to change to the opposite" "when occasion requires it." (The Prince, chap. 18.) Moreover, Avery Plaw notes that in The Prince, Machiavelli commends Ferdinand of Aragon, who gained fame as an exemplary Christian king by attacking Grenada, an "undertaking that was the very foundation of his greatness" and which was funded by "[t]he money of the Church." (The Prince, chap. 21.)[61] Plaw comments, "By relentlessly pursuing a war of conquest, Harry cynically fulfills his dying father's Machiavellian advice to him, to "busy giddy minds / with foreign quarrels" (2 Henry IV, IV.v.213-14). Plaw also notes that while Harry's father "was driven by his guilty conscience to talk endlessly about a crusade to the Holy Land, Harry sets his sights on the more practical target of France."[62]

Plaw does not mention, however, that both Henry IV's anticipated crusade and Ferdinand's actual were against Muslim enemies, whereas Henry V's battle was against a fellow Christian nation. When we consider this crucial detail, the relationship between Canterbury and Henry V parallels the relationship described in Dante's Inferno between the false counselor Guido da Montefeltro and the corrupt Pope Boniface VIII. The damned Franciscan Guido relates that Boniface fought neither "Saracens or Jews / For Christian all were enemies of his" (Dante, Inferno, canto XXVII); Guido is damned for providing Boniface counsel to act treacherously against the Colonna family--does Shakespeare expect any less divine retribution for Canterbury's deceptive use of Numbers 27:8 (see Henry V I.ii.99-100)? Does Henry V resemble Dante's despised Boniface VIII even more than he resembles Ferdinand of Aragon? Is it possible that Shakespeare presents Henry V as even more problematic than Machiavelli's model prince?

In "Power and Corruption in Shakespeare's Plays," I suggested that Henry's nagging guilt concerning Richard III's usurpation and his pious concern for Richard's soul relieves him from the charge of absolute corruption.[63] Plaw is not so charitable toward Harry. Plaw writes that Henry "is trying to buy forgiveness without real penitence, which would entail at very least public recognition of [his father's] crime, if not renunciation of his ill-gotten position. Otherwise, he is just 'imploring pardon,' not repenting."[64] We can speculate what Henry's conscience might feel later, in the wake of his own war crimes. Will he be plagued by the "pangs of an affrighted conscience," what Adam Smith calls "the daemons, the avenging furies, which, in this life, haunt the guilty, which allow them neither quiet nor repose, which often drive them to despair and to distraction"?[65]

As noted above, Shakespeare's Chorus calls Henry "the mirror of all Christian kings," but the Chorus also undercuts Henry's achievements in the play's epilogue, noting that his conquest of France was soon after lost. Sarah Skwire rightly points to the difficulty in ascertaining Shakespeare's position on the various conflicts we have discussed, but I will speculate nonetheless. In light of the bloody consequences of Henry's unjust war against fellow Christians, is Shakespeare suggesting a corruption of Henry's character that goes far beyond what the Chorus initially seems to indicate? Let us remember the Chorus's words' context. The Chorus reports that the youths and men of England are following "the mirror of all Christian kings" (see II.0.1-7). We may easily argue that the perception of Henry as said "mirror" is on the part of those who follow him--not on the part of the Chorus or Shakespeare himself. We should also consider different definitions of the word "mirror." The Oxford English Dictionary quotes the Chorus's above phrase as an example of the definition "a model of excellence; a paragon."[66] But the next definition of "mirror" is "a person or thing embodying something to be avoided; an example, a warning."[67] Does Shakespeare in fact portray Henry as so thoroughly corrupted that he ought to be viewed through the lens of the latter definition?

Endnotes

[57.] Erasmus, The Education of a Christian Prince, trans. Neil M. Cheshire and Michael J. Heath, ed. Lisa Jaradine (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 102. Young cites a different passage.

[58.] R. V. Young, "Shakespeare's History Plays and the Erasmian Catholic Priest," Ben Jonson Journal 7 (2000): 106.

[59.] See David Urban, "Power and Corruption in Shakespeare's Plays," par. 7.

[60.] Erasmus, 106.

[61.] Avery Plaw, "Prince Harry: Shakespeare's Critique of Machiavelli," Interpretation: A Journal of Political Philosophy 33.1 (2005): 23-24.

[62.] Plaw, 23.

[63.] Urban, "Power and Corruption in Shakespeare's Plays," par. 8.

[64.] Plaw, 38.

[65.] Adam Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments III.2.9 (page 118 of Liberty Fund edition).

[66.]"Mirror," definition 1b, Oxford English Dictionary Online.

[67.]"Mirror," definition 2, Oxford English Dictionary Online.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.