Liberty Matters

Standing Armies and Taxation

I’d like to thank Stephen Halbrook for his quotation from Machiavelli about the Swiss -- clearly Machiavelli thought that some free citizens fought all the more effectively because they fought to defend their freedom. I’m still not sure that he thought that this could be stated as a general principle.

I’d like to thank Stephen Halbrook for his quotation from Machiavelli about the Swiss -- clearly Machiavelli thought that some free citizens fought all the more effectively because they fought to defend their freedom. I’m still not sure that he thought that this could be stated as a general principle.I look forward, of course, to discussing these matters with David Womersley in a few weeks time, but I’d like to add yet another topic to that discussion. In his original contribution and in his reply David makes an argument repeatedly which I either can’t understand or don’t agree with. He says that

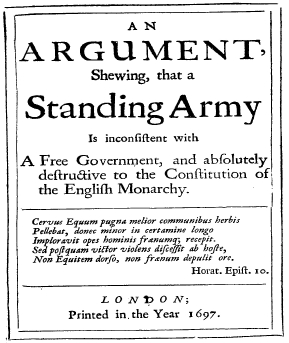

- at the end of the 17th century in England the term standing army is “used much more narrowly to refer to an army that is kept together during peacetime and paid for out of taxation” (his italics);

- “as recently as 1656, and reflecting in Machiavellian style on English experience in the Civil War, James Harrington had dismissed the notion of a standing army supported by taxation as ‘a mere fancy, as void of all reason and experience as if a man should think to maintain such an one by robbing of orchards; for a mere tax is but pulling of plumtrees, the roots whereof are in other men’s grounds, who, suffering perpetual violence, come to hate the author of it’” ;

- “in the autumn and winter of 1697 standing armies⎯ now properly so-called because they had become a permanent part of the resources of the state and were paid for out of taxation⎯ might for the first time be resisted on the grounds of both liberty and frugality”;

- “it is clear that Machiavelli was unable to conceive of armed forces receiving regular salaries paid for out of normal taxation.”

David seems to think that standing armies are characterized by two novel features: 1) they are kept together in peacetime, and 2) they are paid for out of taxation. The first is straightforward -- a standing army simply is an army kept together in peacetime. It is the second that puzzles me, for how else could an early modern army be paid except out of taxation? Of course tax revenues often fell behind expenditures, so armies were funded by borrowing money, but the money was repaid out of taxation. I can think of some exceptions -- sale of office, for example, was used as a major source of revenue in 17th-century France and doesn’t exactly count as taxation. And I suppose Spanish armies were funded by silver from the New World. But elsewhere, unless I am missing something, what paid for armies were taxes. Of course what is peculiar about a standing army is that it requires a regular tax revenue to support it, not exceptional taxes raised at a time of crisis; but I don’t think that that is David’s point, although he does, as we shall see, refer to “normal taxation,” so perhaps it is.

Machiavelli, we are told, “was unable to conceive of armed forces receiving regular salaries paid for out of normal taxation.” As it happens this is wrong. One of Machiavelli’s earliest political texts, dating to March 1503 when he was serving in the Florentine civil service, is entitled Parole da dirle sopra la provisione del danaio. (There’s a translation in vol. 3 of the Gilbert Chief Works, but I won’t vouch for its accuracy.) It is a speech (presumably not to be delivered by Machiavelli himself) calling for the establishment of a Florentine standing army funded out of regular taxation. The argument is simple: although Florence is not currently at war, she might find herself at war at any time. No state can survive if it lacks the means to defend itself against any likely adversary. A Venetian army could be on Florentine territory within two days, Cesare Borgia’s army within eight. (The basis of this concern is of course that both the Venetians and Borgia have an army available in peacetime -- in the case of Venice, a mercenary army.) Only a standing army can deter an invasion; indeed if Florence remains undefended she is bound to be invaded.

It is true that Machiavelli turned later that year to organizing the militia, which was designed to be a force which could be quickly assembled and used against any invader. Evidently this was intended to be a cheaper option than a standing army. But Machiavelli clearly had at one point conceived of armed forces receiving regular salaries paid for out of normal taxation -- and indeed the militia, if it was ordered to go on active service, was to be paid out of taxation.

It is also true that Machiavelli was opposed to professional armies. This was not because they would be standing armies or paid for out of taxation. It was because for most mercenary soldiers and officers peace meant unemployment, and they would thus do anything they could to prevent peace; they also engaged in looting and rapine so that they had something to fall back on if peace broke out. The advantage of the militia was that (apart from a small professional corps of NCOs employed full time) its members would all have peacetime occupations to which they could return. Their interests would thus coincide with those of the population as a whole. This is an application of the republican principle of rotation of office -- a principle also applied in Machiavelli’s militia, where officers were rotated regularly so that troops would not develop a personal loyalty to them.

What then of Harrington? Cromwell’s army had had its pay constantly in arrears. There was enormous hostility to paying those wages out of taxation, and to some extent they were paid by confiscating land from royalists. Harrington was quite right to think that persuading the English to accept a standing army paid for out of regular taxation was almost impossible. But that of course was because England together with Scotland was an island where no invasion could take place without some warning, as it would require the assembly of a large fleet on the other side of the channel. And this peculiar English/British privilege continues to inform the standing-army debates at the end of the 17th century.

I think it is important to understand that there is an Anglo-American tradition of thinking about standing armies and militias which is premised on the absence of any immediate threat of invasion in normal peacetime. The Florentines, as Machiavelli insisted, could not afford to think about the threats they faced in this relaxed fashion -- and he was right, as the events of 1512 demonstrated.

I think the point David makes about the professions is an interesting and important one. But what is surely also important is the social location of the officer corps of the British army in the 19th century -- the younger sons and brothers of landed gentlemen, the cousins of clergymen, they were firmly attached to a social elite which they rejoined when they retired from active service. The army was less a separate profession than the Church or the law, for its officers mixed and mingled with the gentry -- including people like Gibbon -- on a daily basis. It is this intertwined character of the British elite, which one can see in Jane Austen’s novels, which must in part explain Britain’s extraordinary political stability since 1688. Someone must have written a fine book on the differences between the British and the Prussian armies -- perhaps a reader of this can point me to it.

Joseph Stromberg quotes Harling and Mandler on Britain’s “ruthlessly regressive tax system” in 1815. But was it more regressive than tax systems elsewhere in Europe? More regressive than taxes even in Napoleonic France? Certainly for the 17th and 18th centuries the crucial feature of the English tax system was that everyone paid tax -- that nobody was exempt from taxation -- which created a coincidence of interests between legislators and the public, similar to the coincidence of interests created by rotation. This, of course, increased hostility to standing armies at the end of the 17th century; what’s astonishing is that the British high tax system was built on parliamentary consent -- because the costs of empire were thought to be worth paying because they were more than compensated for by the economic opportunities that the empire opened up.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.