Liberty Matters

A Movement Forest Cluttered with Partisan Trees

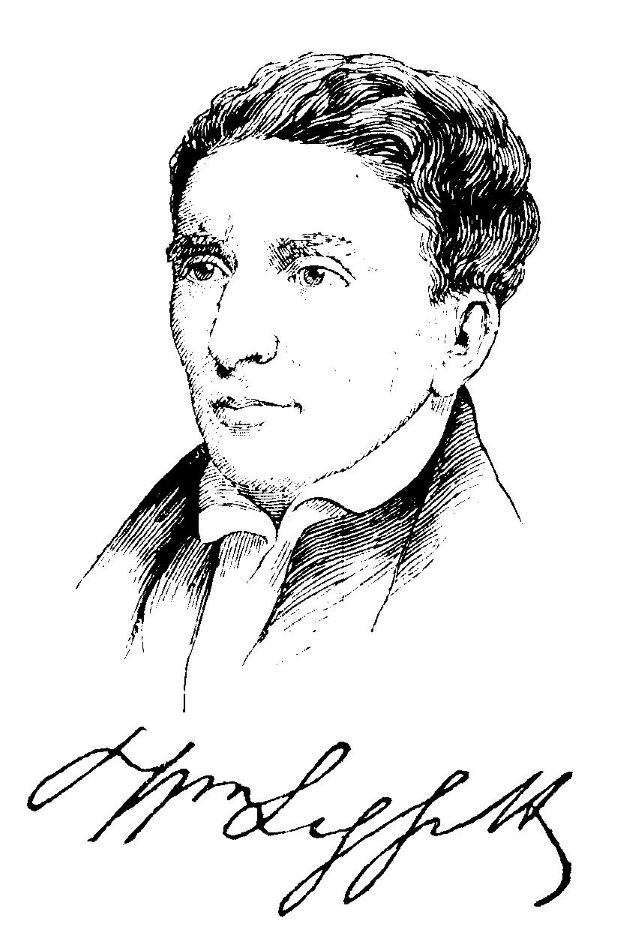

Virtually every secondary source on William Leggett's locofocoism cites its way back to a single article by historian William Trimble published almost exactly one century ago.[47] Trimble was planning a much larger study but never completed it: "This article is collated from a more extensive study, now in manuscript, on the history of the Locofoco party." Interestingly, Trimble's interest was sparked "a number of years ago in a seminar of Professor Frederick J. Turner, who has continued to evince helpful interest." If only Trimble had finished and published the project (I know the struggle!), we may have lived through a very different sort of 20th century. Just imagine if, ca. 1920s-40s, Americans like Albert Jay Nock, Rose Wilder Lane, or H. L. Mencken had a full history of Locofocoism at their fingertips. I cannot say what they would have done with it; but as history actually happened, Trimble's manuscript went neglected and the Locofocos all but disappeared from the record.

And Trimble was really on to something. His Progressive perspective helped identify a movement which bridged the gap between free markets and left-wing social causes. Historians in Trimble's generation understood that the time-worn nationalist narrative peddled by the likes of George Bancroft (our country's original court historian) operated in favor of the ruling class.

The nationalist view treated American history as complicated and messy but always righteous and good. Colonial history was a prelude to the Revolution, and all history after 1776 was the logical and proper unfolding of America's place in humanity's destiny. Nationalist historians emphasized what they saw as a single great creed of mission uniting all Americans across time and space, from the Puritans' "City upon a Hill" to the martyred Abraham Lincoln.

Progressives, by contrast, emphasized the deep and lasting conflicts in American life. Informed by a mix of Marxist concerns about economic power and libertarian concerns about state power, their best histories read like Trimble's article on locofocoism. They recognized how deeply interconnected political and economic power were, and they mercilessly applied their first principles to whatever question they were studying.

The Progressives' main mistake, though, was idealizing the past into clean categories of heroes and villains: Piedmont vs. Tidewater, Republicans vs. Monarchists, Democratic-Republicans vs. Federalists, Democrats vs. Whigs, Labor vs. Capital, and so on. Progressive histories often read like comic books, and the narratives could get fairly cartoonish. Trimble's article on the Locofocos is no different. He lauded Locofoco Ely Moore for being "the first president of the New York General Trades' Union and also of the National Trades' Union," and the man John Quincy Adams called "the prince of working-men." He painted the New York Locos as pure heroes organizing for the people, but as we have already seen, the story is far more complex and far less noble.

For Trimble the Locofocos were the clear forerunners for his own school of progress, and if he had followed the story through he could have really had something there. But one key error spoils the project. Trimble limited his perspective to the Locofoco Party and therefore missed the movement. For all their keen attention to political power, to Progressives and most historians since, history is really about political activity and anything not apparently useful to that effect is relatively useless.

It seems astonishing that despite the field-quaking changes in the historical profession since then, so few have bothered to expand on Leggett and locofocoism beyond Trimble's article and perhaps a few primary sources. The sad fact remains: except for a few stragglers from the old labor left, almost no historians have any interest in people like Leggett, and his story has gone largely untold. Trimble helped along the forgetting process with conclusions like this: "The Equal Rights or Locofoco party which this faction organized, though it proved insignificant in number of adherents and in duration of existence, nevertheless has a distinct place in American political history." Distinct, sure—but worth remembering? Most historians who might have read Trimble apparently think not.

Even those left-wing labor historians who admire the Locofocos have made this same move—they laud locofocoism as a forerunner to the labor movement and even the New Deal, which they love so much, while either grievously misunderstanding or conveniently ignoring the ultra-libertarianism. They praise the party for aiding labor but bury it as soon as the true movement began. Telling that tale requires forsaking the state as the central focus of history, and precious few historians do that.

So let's hear it for Liberty Fund! If we were not taking the time to remember Leggett, I fear no one else would.

Endnotes

[47.] William Trimble, "Diverging Tendencies in New York Democracy in the Period of the Locofocos," The American Historical Review 24, No. 3 (Apr. 1919): 396-421. Available online at JSTOR, <www.jstor.org/stable/1835776>.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.