Liberty Matters

Restoring Trust in the Democratic Process

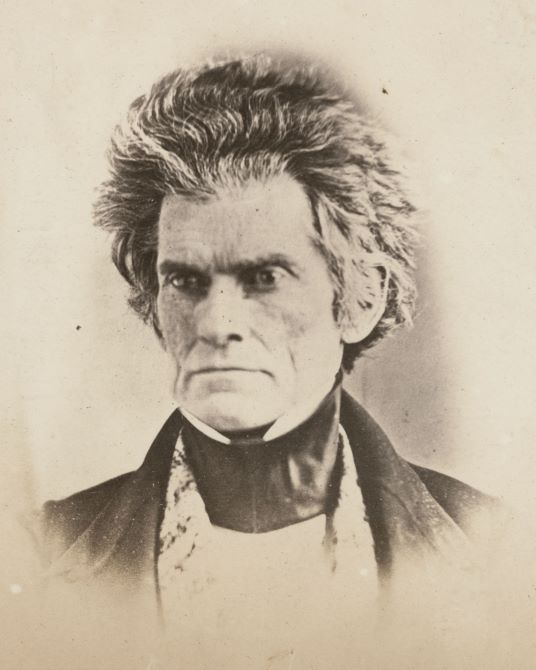

Thank you to Keith Whittington, John Grove, and Jay Cost for their thoughtful observations on Calhoun’s political theory, the extent to which it was or was not separable from his defense of slavery, and its relevance to our own troubled times. Some thinkers resonate with us because their arguments reinforce our own assumptions and judgments. Other theorists -- and for me this includes Calhoun -- are valuable because they challenge our assumptions and judgments, forcing us to see and think more clearly even if we remain unpersuaded.

John observed (and Keith agreed in response) that Calhoun was least original when he defended slavery, where his arguments “were all second hand,” in contrast to the rigor and originality with which he analyzed political and constitutional questions. I believe John’s observation is correct, but in a tragic sense. For it was precisely because Calhoun was a political leader of national stature, and a force to be reckoned with in constitutional debate, that he magnified the political impact of a second hand “positive good” defense of slavery. His endorsement – to a much greater degree than the lesser-known proslavery theorists he borrowed from -- helped give Southern political leaders a good conscience to engage in an uncompromising defense of slavery.

Where Calhoun was most original and penetrating was in his critique of the “normal” democratic process. He had a keen eye for the corruption, the partisanship, and the winning coalition’s indifference to the interests of everyone else that so frequently characterizes our policymaking. When I first looked into the political process that produced the 1828 “Tariff of Abominations” (which originally motivated Calhoun’s nullification remedy), what struck me was how unsurprising that process appears from our contemporary perspective. We might be inclined to respond, “that is how the sausage is made, get over it.” Calhoun was not satisfied with that answer. He believed that fidelity to republican principles demanded something better. In this sense I agree with John Grove that Calhoun’s vision of politics was not amorally Hobbesian.

Jay Cost wrote in his post that Calhoun underestimated the potential of democratic politics “to secure equitable treatment in the Madisonian system.” To trust in the Madisonian constitutional vision, which excludes extreme remedies like nullification, means in practice to rely upon our regular political and electoral processes to replace bad laws with better ones; or for that matter, to replace bad presidents with better ones. This may seem merely a civics textbook platitude. But I believe it requires great faith and restraint, when one finds oneself on the losing side on matters of great importance, to trust that the errors and injustices of majority rule can be remedied by assembling or electing a different majority in the future.

If, then, we reject Calhoun’s nullification (not to mention even more extreme responses to the imperfections of our democracy), then I believe we must commit ourselves to restoring trust in the democratic process, and patiently working to improve that process, at a time when this is no easy task.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.