Liberty Matters

Moral Stance verses Moral Sense

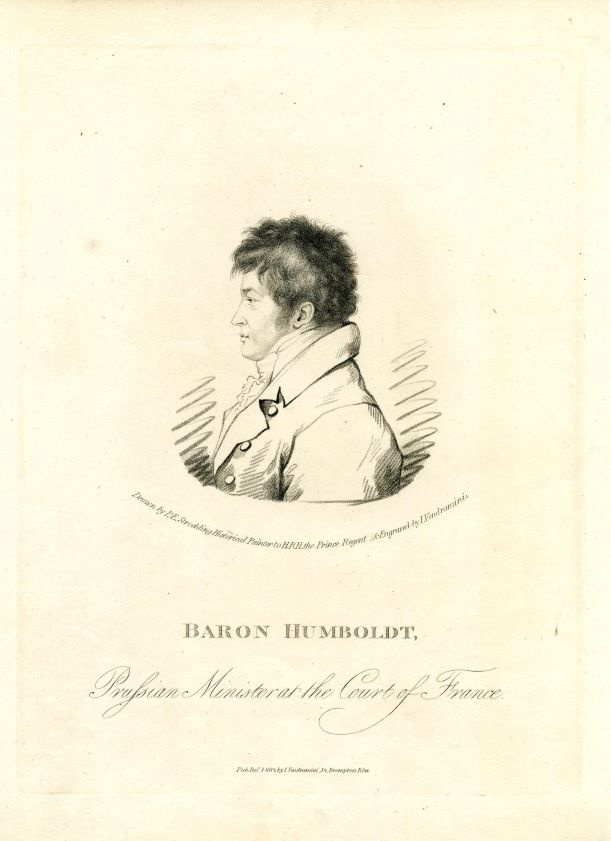

It does not come as a big surprise that modern constitutions have a hard time if they attempt to suit both the freedom individuals ask for and the moral sense democratic constitutions nourish. In light of the lead essay and the addenda as regards security and the undermining of human morality in our WEIRD states, it might be worth turning to morality as a safeguard of liberty in a constitutional state, classic or modern. Of course, Humboldt dealt only with the classic version, for he did not live to see its modern democratic heir. Humboldt saw in the “State constitution … a necessary evil” (105), not at all a safe haven, neither for liberty nor for morality. In order to provide its citizens with the security they need to attain their true end, the state has to assure them “legal freedom,” threatened not “by all such actions as impede a man in the free exercise of his powers, and in the full enjoyment of all that belongs to him, but only by those which do this unrightfully.” (67) Humboldt was aware that he “who utters or performs anything calculated to wound the conscience and moral sense of others, may indeed act immorally; but, so long as he is not chargeable with obtrusiveness in these respects, he violates no right.” (69f.) Humboldt justifies the toleration of immoral behaviour – even if it is calculated – with the observation that “it was free to those who were exposed to the influence of such words and actions to counteract the evil impression on themselves with the strength of will and the principles of reason.” (70) The strength of his argument is that it serves two masters. It safeguards freedom against accusations claiming its exercise to wound the moral sense of others. It also makes clear that the immoral performances of our fellow citizens contribute to the “variety of situations” which allow us to develop moral stance, and thus help man in the “harmonious development of his powers” (13), simply by “the strength of will and the principles of reason.” It is the moral stance of the individual, not the moral sense of others, that Humboldt guards.

It does not come as a big surprise that modern constitutions have a hard time if they attempt to suit both the freedom individuals ask for and the moral sense democratic constitutions nourish. In light of the lead essay and the addenda as regards security and the undermining of human morality in our WEIRD states, it might be worth turning to morality as a safeguard of liberty in a constitutional state, classic or modern. Of course, Humboldt dealt only with the classic version, for he did not live to see its modern democratic heir. Humboldt saw in the “State constitution … a necessary evil” (105), not at all a safe haven, neither for liberty nor for morality. In order to provide its citizens with the security they need to attain their true end, the state has to assure them “legal freedom,” threatened not “by all such actions as impede a man in the free exercise of his powers, and in the full enjoyment of all that belongs to him, but only by those which do this unrightfully.” (67) Humboldt was aware that he “who utters or performs anything calculated to wound the conscience and moral sense of others, may indeed act immorally; but, so long as he is not chargeable with obtrusiveness in these respects, he violates no right.” (69f.) Humboldt justifies the toleration of immoral behaviour – even if it is calculated – with the observation that “it was free to those who were exposed to the influence of such words and actions to counteract the evil impression on themselves with the strength of will and the principles of reason.” (70) The strength of his argument is that it serves two masters. It safeguards freedom against accusations claiming its exercise to wound the moral sense of others. It also makes clear that the immoral performances of our fellow citizens contribute to the “variety of situations” which allow us to develop moral stance, and thus help man in the “harmonious development of his powers” (13), simply by “the strength of will and the principles of reason.” It is the moral stance of the individual, not the moral sense of others, that Humboldt guards.If Tortarolo is right – and I am afraid he is – when saying that in our days “a massive public network of institutions and agencies […] have taken much if not all the place that Humboldt assigned to the moral human being,” then it will be a difficult to pave the way for the moral human being to find a way back to the place Humboldt had reserved for him.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.