When I blogged about Pierre Goodrich's copies of Darwin, I mentioned his long-standing interest in the history of science. Finding a modern (1941) translation of William Harvey's masterwork, De Motu Cordis (The Motion of the Heart) among his collection emphasizes that this interest was more than casual. And with Valentine's Day just around the corner, I couldn't resist the joke.

The Reading Room

De Motu Cordis: From the Liberty Fund Rare Book Room

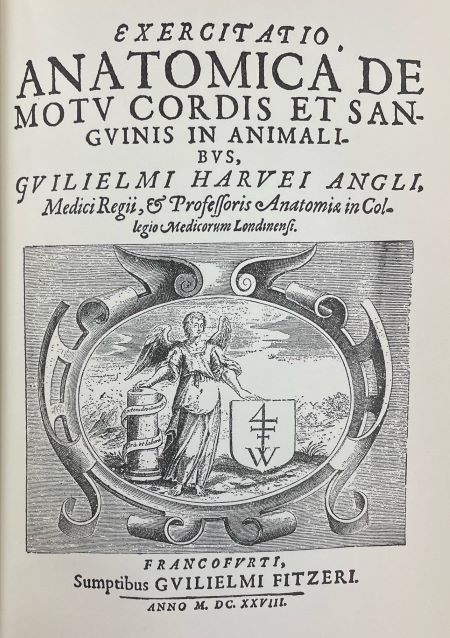

Not lavishly bound, Goodrich's copy of Harvey's book is a simple and clear translation, produced for the purpose of reminding people of Harvey's important contributions to medical knowledge. As the cover states, the book is a "historical milestone," and "one of the really great contributions to medicine," and "one of the finest examples of deductive reasoning."

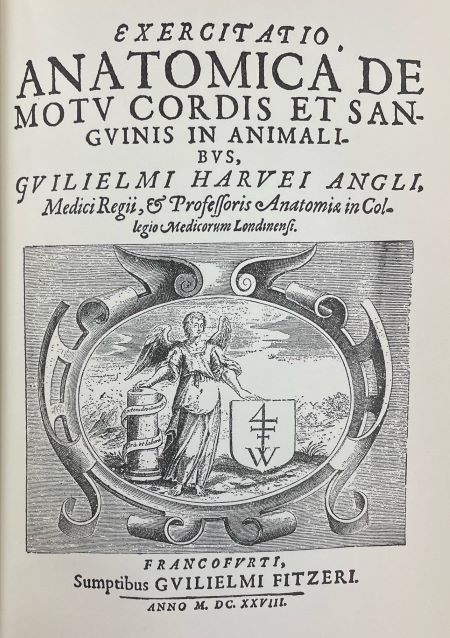

Harvey's accomplishment was to describe the circulation of the blood more thoroughly and accurately that any previous attempts. The prevailing belief when the wrote came through Galen--that blood was created in the liver, passed through the heart, and was used up by the body. Harvey noted the one way valve structures of the human circulatory system and that, combined with a (frequently wrong, but helpful in this instance) adherence to Aristotle's insistence on "cycles" and a fearless approach to dissection and experimentation, led to his observations.

Michael Servetus had made strides towards a more accurate description of pulmonary circulation about a century before Harvey, but had been burned at the stake by John Calvin for his heretical stance on the trinity. His books were burned as well, and only 3 copies of his Restitutio survived. So Harvey's work was done without the learning of Servetus, and with the knowledge of the risks taken by those--like Servetus or Galileo--whose work in science brushed up against theological subjects.

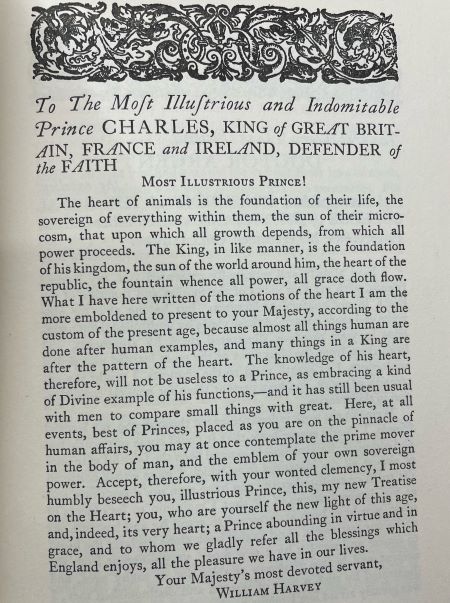

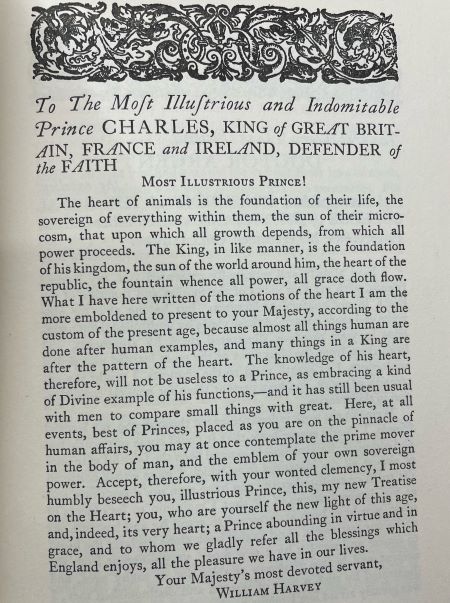

It is perhaps with these risks in mind that Harvey carefully dedicated his book to King Charles I. He may have been hoping for some royal protection, or at least the appearance of probity despite his book's overturning of received wisdom and the shock that accompanied any discussion of dissection in the period.

And while Harvey was under no physical threat, his little book did damage his reputation for quite some time. The medical establishment was unwilling to accept the change in thinking and in medical practice that Harvey's observations would have required. Rather than change their ways, they preferred to denigrate Harvey's work. It took a long time for Harvey's observations to be acknowledged as true, and even longer for them to be seen as useful.

And while Harvey was under no physical threat, his little book did damage his reputation for quite some time. The medical establishment was unwilling to accept the change in thinking and in medical practice that Harvey's observations would have required. Rather than change their ways, they preferred to denigrate Harvey's work. It took a long time for Harvey's observations to be acknowledged as true, and even longer for them to be seen as useful.

Harvey's accomplishment was to describe the circulation of the blood more thoroughly and accurately that any previous attempts. The prevailing belief when the wrote came through Galen--that blood was created in the liver, passed through the heart, and was used up by the body. Harvey noted the one way valve structures of the human circulatory system and that, combined with a (frequently wrong, but helpful in this instance) adherence to Aristotle's insistence on "cycles" and a fearless approach to dissection and experimentation, led to his observations.

Michael Servetus had made strides towards a more accurate description of pulmonary circulation about a century before Harvey, but had been burned at the stake by John Calvin for his heretical stance on the trinity. His books were burned as well, and only 3 copies of his Restitutio survived. So Harvey's work was done without the learning of Servetus, and with the knowledge of the risks taken by those--like Servetus or Galileo--whose work in science brushed up against theological subjects.

It is perhaps with these risks in mind that Harvey carefully dedicated his book to King Charles I. He may have been hoping for some royal protection, or at least the appearance of probity despite his book's overturning of received wisdom and the shock that accompanied any discussion of dissection in the period.

And while Harvey was under no physical threat, his little book did damage his reputation for quite some time. The medical establishment was unwilling to accept the change in thinking and in medical practice that Harvey's observations would have required. Rather than change their ways, they preferred to denigrate Harvey's work. It took a long time for Harvey's observations to be acknowledged as true, and even longer for them to be seen as useful.

And while Harvey was under no physical threat, his little book did damage his reputation for quite some time. The medical establishment was unwilling to accept the change in thinking and in medical practice that Harvey's observations would have required. Rather than change their ways, they preferred to denigrate Harvey's work. It took a long time for Harvey's observations to be acknowledged as true, and even longer for them to be seen as useful.