Liberty Matters

Slavery, Capitalism, and the New Moralism

I’ve been aware of Phil Magness’ views on the New History of Capitalism for many years, even before 2018, when Magness wrote a chapter on the subject in a book he and I co-edited called What is Classical Liberal History? Magness argued then, as he does now, that the New History of Capitalism is guided by strong ideological priors. Since 2018, the most consequential development in this field of study has been the appearance of the 1619 Project, which Magness has also rebutted at length. I see the New History of Capitalism, the 1619 project, and the increasing policing of historians’ language about slavery (enslaved persons, not slaves, etc) as allies in a kind of new moralism that seeks to control the historiography of slavery and capitalism. In short, scholars who hold these views believe that they are making moral contributions by helping us see the history of slavery and capitalism in the right way. If the worst elements of the past can be shown to have been born out of capitalism, or gave rise to capitalism, or even were capitalism, then capitalism in the present day must be marred by its historical sins and alternatives must be considered. More than an ideological project, then, I believe this is a moralizing project, as the supporters attempt to label their opposition as more than factually wrong, but morally wrong for expressing opposing views.

Magness suggests that there isn’t much novelty in the arguments proffered by the New History of Capitalism. This may be true, but there is a sense in which their general attitude and focus is quite new to scholars under the age of sixty. If you would have told American historians twenty years ago that the next big trend in historiography was American capitalism, you would have been laughed out of the room. Economic history then had few practitioners in history departments. History departments were much more likely to offer courses on communism than capitalism. The popularity of the New History of Capitalism and of the 1619 Project would have seemed unlikely. Historians in decades to come will still be asking how and why these developments came about. The usual explanation of the 2008 economic crisis as the catalyst seems insufficient. There are deeper cultural and institutional reasons.

In a way, I’m a pessimist about historiography in general. The best-written and best-argued histories seldom dominate historiographical currents. Rather, success in this regard is just as likely to be determined by the position and power of the writers and their ability to appeal to their audiences’ a prioris. Elite institutions, themselves some of the greatest beneficiaries of capitalism, play an outsized role in shaping academic currents. Magness considers Baptist, Beckert, Johnson, and Rockman as the core figures of the New History of Capitalism. These scholars all teach at elite universities, and in fact, they all taught at those universities before their leading works were published. No doubt the prestige of a Harvard, Brown, or Cornell helped these authors find a publisher and an audience and still gives them a perch to spread their ideas. They are well-funded to organize conferences on these topics and well-positioned to direct dissertations that will help spread these ideas. Their books win awards even while their research is challenged and subject to criticisms that would sink lower-placed academics. The opposition to the New History of Capitalism that one finds in academic journals comes from senior scholars, raised in the empirical traditions of the 1960s and 1970s. Younger scholars who oppose the new orthodoxy are ostracized. This is why, from a liberal perspective, Magness’s dissenting voice is so important.

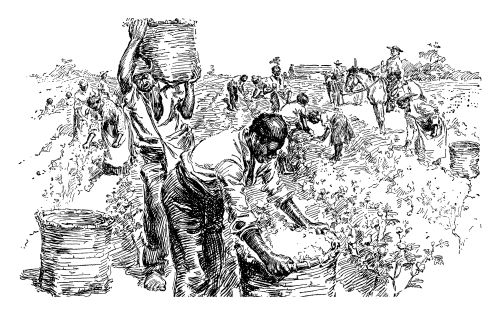

Magness addresses the best-known works in the New History of Capitalism, and he suggests that the Cotton Thesis is at the core of their thought. But the powerful anti-capitalist perspective in studying the history of American slavery extends well beyond studies of cotton. Even if historians sympathetic to the New History of Capitalism read Olmstead and Rhode and rejected the Cotton Thesis and the larger idea that slavery made the West rich, they would still be united in seeing greed and coercion as essential elements of capitalism responsible for the rise of American slavery. Dissenting historians cannot disabuse them of the idea that capitalism is intimately connected to slavery.

Nevertheless, there are some positive developments in this. The New History of Capitalism has encouraged an increased interest in the history of slavery, capitalism, and the two together, and this has yielded important studies. Generally, the narrower the study, and the less grand its aims, the better these works have been, so that dissertations about slavery in particular states or cities are still well-grounded, while larger nationally-focused works reach for the moral heights.

For example, there is brewing a historiographical revolution in how we see slavery in the Northern states, with many good works published on the topic in the past few years. Relatively few of these are explicitly part of the New History of Capitalism, even if they generally agree with its aims and conclusions. In my own work on slavery in New York (The Slow Death of Slavery in Dutch New York [Cambridge University Press, 2024]), I argue against the staple interpretation by showing that slavery was viable and profitable to slaveholders even in wheat production, not just in the traditional staple slave crops of sugar, tobacco, and cotton. I argue, moreover, that slaveholding was always a moral, or rather, immoral choice, and not entirely determined by geography or demography. No one had to own slaves because their land was best for cotton cultivation, and no one had to own slaves because their colony had few available free laborers. They choose to own slaves instead of engaging wage labor. From the beginning, slavery in America was an attempt to avoid the costs, including the turnover costs, of wage labor.

I find the use of “capitalism” in these discussions to be so loaded with ideology and anachronism that it is no longer of much use, except maybe only as a description of the field itself. Scholars who claim to study slavery and capitalism are those who study forced labor, markets, and the economy. What defines capitalism? Is it markets, wage labor, property rights, lack of regulations, or something else? Markets must be a feature of capitalism, but markets alone do not make an economy capitalist. Good socialists are quick to remind us that markets exist in socialist economies as well. It is not true that because there were markets for slaves in America that American slavery was capitalist. There were markets for slaves in the ancient world, and I don’t think it’s fair to describe any ancient society as capitalist. Nor are owners of capital, i.e. capitalists, always the same as those who support free markets and wage labor. Those who own slaves own capital, but I believe it does not follow that all slaveholders are capitalists.

Slave labor in America was one kind of input in an economic system that could be broadly considered capitalistic, but how capitalistic it was depends on the standpoint of the observer. To a true anti-capitalist, everyone to the right of Stalin is a capitalist, and it is common among anarchist-minded libertarians to divide the world into the elect few freedom lovers and reprobate masses of statists. History, like ideology, is usually messier than this. In my research on slavery in New York, I discovered that slaves were often paid for work, either when they were rented out, or as motivation for working harder for their owners. Slave labor merged with wage labor and sometimes transformed into wage labor. In some cases, the incentives of wage labor were responsible for bringing about or speeding up the end of slave labor arrangements.

As noted above, antagonism towards markets, a hallmark of the New History of Capitalism, is often combined with a progressive language movement. It is not a coincidence that all these developments have arisen together. Just like it was a surprise to many to see historians studying capitalism, it would have been difficult to imagine a decade or so ago that a word like “slave,” which has been in the English language for at least a millennium, would suddenly become “problematic.” Books written merely a decade ago, even by the most progressive scholars, could now be labeled insensitive if they were published today. Language changes, and offensive language does exist, but the speed with which the “language authorities” have selected the new appropriate language is more than a little contrived. One’s willingness to use the new, and ever-evolving language, is a signal of belonging to the new moral project. Those who disagree are, as one recent review suggested, acting in a “harmful and offensive” manner. Likewise, by coining new terms to link capitalism and slavery, the New History of Capitalism is waging a rhetorical campaign. Beckert coined “war capitalism” and he and Seth Rockman have a book titled “slavery’s capitalism.” The term “racial capitalism” dates to the early 1980s, but is used more now than ever. These kinds of terms are far from neutral and they bring more confusion than clarity to the debates.

Writers in the new moralist school of slavery and capitalism are constantly reminding their readers of the immorality of the pair. One of the traditional virtues of a historian is being dispassionate. However, history writing always requires empathy with the human condition and there are certain subjects like slavery that allow or even require historians to make a clear moral stance. But in many newer works on slavery, there is moral judgment on every page. Since no one reading these books thinks slavery was good, the constant moralism appears more as a signal of the author’s desire to be understood as a good person than as a necessary element of the presentation.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.