Liberty Matters

Hume and Rousseau’s Differing Conceptions of Liberty

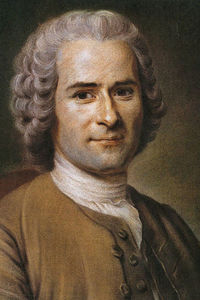

David Hume and Jean-Jacques Rousseau had high opinions of each other’s works. Given their close (but subsequently soured) relationship, it is surprising that there are no signs of mutual influence in their moral and political thought. Rousseau even claimed that Pierre Bayle was the only skeptic of his time. According to Richard Popkin, this means Rousseau “never looked at Hume’s philosophical works, or sought to find out what another skeptic had to say.”[1] Nevertheless, the value of liberty is at the center of their thought. They both maintain that, in promoting public good, the end of government has to be the preservation of liberty. The disparity of their ideas results in their different conceptions of the apparatuses that can best enable conditions for liberty. The key to understanding their contrasting views consists in the relation between liberty and sovereignty.

Rousseau contended that maintaining a free state requires reciprocal support between freedom and equality.[2] Unlike Hume, Rousseau construed equality as a necessary condition for liberty since it yields the independence that serves as the essence of human freedom. Yet, only male citizens can enjoy such equality—Rousseau excluded women from the citizenry due to their alleged inability to conduct public affairs.[3] Hume’s approach, alternatively, is to maintain the dynamics of the competition between liberty and authority.[4] He claimed that all citizens must retain “a right of self-defense” against authority, that is, “a power of resistance.” He argued on this basis that “the same necessity of self-preservation, and the same motive of public good, give them the same liberty in the one case as in the other.”[5] This right, in his view, is meant to prevent the rise of an absolute government. However, given the growth of popular discontent and the prevalence of the Whig theory of resistance (which was based on a contractual theory of political legitimacy) in his time, Hume was skeptical about the purported criteria for judging when such resistance may lawfully occur.[6] In sum, comparing the two thinkers’ approaches to the end of government has already shown us the disparity in their ways of conceiving the ideas of liberty. As we shall see, Rousseau’s emphasis on the citizens’ independence paves the way to his conception of popular sovereignty as the best means to preserve liberty. Hume’s contrast of liberty with authority, nevertheless, underscores the necessity of checks and balances.

It has been argued that Hume does not have a theory of sovereignty[7] and his ground for political authority arises from the “opinion of mankind.”[8] That is to say, a government’s authority comes from the public’s belief in its right to rule, rather than any abstract theory of contract. Hume’s view resulted from his skepticism about the natural law tradition to which Rousseau belonged. For Hume, there was no historical evidence to prove the existence of such covenants. Moreover, natural law theories could not explain what motivated people to obey such laws. In other words, there are no immutable and overarching rights to both authority and liberty. What opinion reflects are the norms of judgment gleaned from conventions. It is therefore unsurprising that Hume never attempted to explicitly define the idea of liberty—its meaning only makes sense when understood in the custom and habit that enable it.[9]

The rise of English liberty is Hume’s prized example. Eighteenth-century Britain enjoyed the greatest liberty among other European nations because of its mixed constitution and representative politics.[10] But a representative government alone could hardly advance and preserve liberty to such a degree. In Hume’s historical writing, Britain’s case demonstrates that liberty arose from its persistent struggle with authority, most notably reflected in the confrontation between the Parliament and the Crown. The evolution of the mixed constitution attested that this process of using power to check power led to the convention in favor of liberty. This also means liberty, in its robust form, was not an abstract idea, nor was it rooted in any rational system of rights. Instead, it was enabled and safeguarded by an assortment of political customs and apparatuses. In Britain, this further led to the civil liberty that allowed commerce to thrive and the liberty of the press.[11]

Hume indicated that civil liberty can arise from both republic and civilized monarchy. This is contrary to Rousseau’s view that only a republican government can yield such freedom owing to its commitment to popular sovereignty. For Hume, civil liberty amounts to the security of persons and properties, which can also be achieved under a monarchical government as long as its institutions and legislation are designed to balance different branches of power. Sovereign power no longer threatened the citizenry, which enabled them to freely pursue wealth. In turn, merchants could elevate their status through purchasing titles; this means to honor encouraged the development of commerce. Since honor was the chief principle of monarchy, maintaining civil liberty would, in fact, benefit the civilized monarchies in modern Europe.[12] The checks and balances of power, in this scenario, not only relied on the rule of law but also the liberty of the press. From this perspective, the citizenry exercised their power not through Rousseauean popular sovereignty, but through the influence of public opinion. The liberty of the press would further encourage diverse opinions: “All the learning, wit, and genius of the nation may be employed on the side of freedom, and every one be animated to its defence.”[13] It is a pluralist civil society as such that preserves liberty. In this regard, the perpetual struggle between liberty and authority actually yields the political dynamics to sustain the former. Hence in a Humean free state, liberty enables liberty.

While Hume deemed the contest between liberty and authority insoluble, Rousseau argued that the two can be reconciled by submitting to the general will under a republican government. His conception of liberty is the key to differentiating his view from that of Hume. Although Hume would not deny that liberty means to be free from domination,[14] he would object to Rousseau’s view that this is only possible through popular sovereignty. This explains why he contended that liberty necessitates equality—the idea of popular sovereignty denotes the equal status of citizens. On this basis, given that the citizenry form the general will, individual citizen’s submission to this supreme authority does not constitute a state of domination. They still retain their freedom since their individual wills are incorporated into the general will. Rousseau therefore made an original contribution to the question of liberty and authority by associating liberty with the idea of popular sovereignty.[15]

Liberty and authority are no longer in conflict as Rousseauean citizens’ liberty includes the exercise of power—popular sovereignty means authority ultimately remains in their hands. Rousseau’s theory of sovereignty only becomes possible as he explicitly defined four types of liberty: natural, civil, moral and democratic. Natural freedom only exists in the state of nature where one is their “own master” and “sole judge” of their self-preservation.[16] One exchanges this freedom for civil liberty when one enters into a political society through the social contract and becomes a citizen. They retain the right to private property and are free from coercion from the state or others. Their freedom of choice is subject to the general will’s regulation. That said, moral freedom enables them to remain their own master, as it suggests that they voluntarily “prescribe” themselves the law to obey the general will. This obedience ensures that they would not become the slave of “the impulsion of mere appetite.”[17] To prevent the general will from dominating individual citizens’ will, Rousseau introduced the idea of popular sovereignty, which necessitates a form of democracy for citizens to legislate for themselves. In other words, while each citizen can enjoy civil liberty, this democratic freedom applies to the citizenry.[18] Considering that sovereignty is “inalienable” and “cannot be represented,” all laws must be rectified by “the people” taken as a whole.[19]

As a result, while Humean citizens can only influence the government’s authority through public opinion, Rousseauean citizens have a direct connection between their collective will and the legislation under a republican government. Nevertheless, comparing Hume’s and Rousseau’s conceptions of liberty does not show which one should prevail. Instead, the disparity in their thought suggests that no single form of government can perpetually guarantee liberty. Hume’s emphasis on opinion demonstrates the power of ideas; hence freedom of thought and expression fosters greater degrees of liberty. Rousseau’s conception of popular sovereignty underscores the value of equality and autonomy, which requires proactive civic participation. Altogether, liberty based on value pluralism and egalitarianism remains an invaluable legacy of Enlightenment thought for our world today.

Endnotes

[1] Richard Popkin, “Did Hume or Rousseau Influence the Other?” Revue internationale de philosophie 32, no. 124/125 (1978): 297–308.

[2] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, “Of the Social Contract,” in Rousseau: The Social Contract and Other Later Political Writings, ed. Victor Gourevitch, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 80 [hereafter as SC]; “Discourse on Political Economy,” in ibid., 266. David Lay Williams, “Rousseau’s Ancient Ends of Legislation: Liberty, Equality (and Fraternity),” in The Cambridge Companion to Rousseau’s Social Contract, ed. David Lay Williams and Matthew W. Maguire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2024), 113–37.

[3] Helena Rosenblatt, “On the ‘Misogyny’ Of Jean-Jacques Rousseau: The Letter to D’Alembert in Historical Context,” French Historical Studies 25, no. 1 (2002): 91–114; Geneviève Rousselière, “Rousseau’s Theory of Value and the Case of Women,” European Journal of Philosophy 29, no. 2 (2021): 285–98.

[4] David Hume, Essays, Moral, Political and Literary, ed. Eugene F. Miller (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1987), 40–1.

[5] David Hume, A Treatise of Human Nature, ed. David Fate Norton and Mary J. Norton, vol. 1, 2 vols. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 3.2.10.16. [Hereafter as T]; The History of England from the Invasion of Julius Caesar to the Revolution in 1688, ed. William B. Todd, 6 vols. (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1983), 5: 380–8.

[6] T 3.2.10.1.

[7] Paul Sagar, The Opinion of Mankind: Sociability and the Theory of the State from Hobbes to Smith (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018). (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018).

[8] T 3.2.9.4; Essays, 32–3.

[9] T 3.2.5.11, 3.2.8.9, 3.2.9.1, 3.2.10.2; Essays, 465–87; David Hume, An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals, ed. Tom L. Beauchamp (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), Appendix 3.8. [hereafter as EPM]

[10] History, 5: 59.

[11] History, 5: 126–34; 6: 367; Essays, 9–13, 87–96. David Wootton, “David Hume: ‘The Historian,’” in The Cambridge Companion to Hume, ed. David Fate Norton and Jacqueline Taylor, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 476–7.

[12] Essays, 10–1, 92–4.

[13] Essays, 12–3.

[14] Michael Locke McLendon, “Rousseau’s Negative Liberty: Themes of Domination and Skepticism in The Social Contract,” in The Cambridge Companion to Rousseau’s Social Contract, 88–112.

[15] SC, 49–51. Robert Wokler, “Rousseau’s Two Concepts of Liberty,” in Rousseau, the Age of Enlightenment, and Their Legacies, ed. Christopher Brooke and Bryan Garsten (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012), 170–1.

[16] SC, 42.

[17] SC, 53–4.

[18] SC, 57, 114. Matthew Simpson, Rousseau’s Theory of Freedom (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2006), Ch. 4.

[19] SC, 70, 114–5.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.