Liberty Matters

Contrasting Views of Liberty in Rousseau and Hume

Introduction

In this essay, I will contrast two views on liberty found in the works of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and David Hume. These views are embedded in very different stories about the nature of liberty and its unfolding over the course of human history, giving rise to fundamentally different assessments of the roles played by exchange, markets, and commerce in bringing liberty to the modern world[1] They lead to quite different conclusions about what needs to be done to realize and protect liberty in the present and future.[2]

Rousseau’s Story of Liberty

Chapter 1 of the Social Contract opens with the statement: “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.” (156) What does he mean by this paradoxical statement? To answer, we must go back to the conjectural history that Rousseau develops in the Second Discourse. He begins by noting that animals are “ingenious machines,” given senses by nature for self-preservation. Humans, too, are machines, but with a significant difference: “nature alone does everything in the operations of an animal, whereas man contributes as a free agent to his own operations.” (p. 52) Animals must obey what nature commands through the senses. Humans feel the impetus of nature but, unlike animals, can go along or resist. In the awareness of freedom lies the spirituality of the human soul and the faculty of self-perfection. To be a free individual for Rousseau is to be the author of one’s own actions. To be unfree means to be dependent upon the actions and judgements of others. Loss of freedom essentially means to be dependent on others for one’s material and emotional well-being.

The hypothetical evolution of human civilization that Rousseau describes in Part Two of the Second Discourse is the story of the fall from natural liberty that originally existed in the state of nature. From isolated independent individuals and small families living in primitive conditions to small bands of wandering families to wealthy societies with laws and government to protect property, new forms of social organization make humans more interconnected and productive, and, as a result, more dependent upon one another. Over time, they learn to act collectively together and to solve problems in innovative ways. They discover the advantages of the division of labor and invent a variety of technologies, such as language, metallurgy, and agriculture. For Rousseau, there is a steep cost to liberty on the road to civilization. As social progress binds humans closer together materially and emotionally, humans are stripped of that natural freedom found in nature. The expansion of the division of labor and the growth of markets, exchange, and commerce may free us from the material limitations of nature, but they also foster conditions that enslave us to the activities and evaluations of our fellows. We can no longer take care of ourselves physically, nor can we rely upon ourselves for a proper evaluation of who we are or what we value. In becoming social creatures, we leave nature behind and become shadows of our authentic selves. We become unfree and miserable individuals, living in a society of wealth and abundance.

What does Rousseau see as a way out of this world of dependency and unfreedom?[3] In the Social Contract, Rousseau sets out to solve this problem, taking “men as they are and laws as they might be.” (p. 156) He puts the problem succinctly: We must “Find a form of association that defends and protects with all common forces the person and goods of each associate, and, by means of which, each one, while uniting with all, nevertheless obeys only himself and remains as free as before” (p. 164) How is this done? By placing ourselves and all our powers under the direction of the “General Will,” and by receiving all others in the political community as indivisible parts of the whole. Living under this General Will protects us from all personal dependency on others, the hallmark of slavery. By participating in this social contract, humans replace their natural freedom as authors of their own actions with a civic freedom where they live under a collective will for the public good that they have authorized. In Book II, Chapter 3 of the Social Contract Rousseau explains the complexity of this process of realizing civic freedom through the General Will in a well-organized political community. How can citizens be assured that citizen deliberations on the public good (the General Will) always be right and tend toward practical utility? Two conditions must be met: the deliberating body of citizens must be “sufficiently informed” and there must be no communication among citizens in thinking about the public good. The General Will is realized not through the bargaining of self-interested citizens but through the impartial and careful reflection of all citizens. Through introspection citizens discover and become authors of the General Will. As in nature where a natural man is free because he follows his own will, citizens are free in society because they authorize and follow freely the General Will.[4] Of course, one still has a private will or a will as a member of a private association, but these wills come under the direction of the General Will of the community under the terms of the social contract. If these two lesser wills conflict with public utility, the General Will can “force people to be free.” (see Social Contract Part I Chapter 6: 167) This conclusion about forcing people to be free is meant to shock readers about the difficulties of being free individuals in society.

Hume’s Story of Liberty

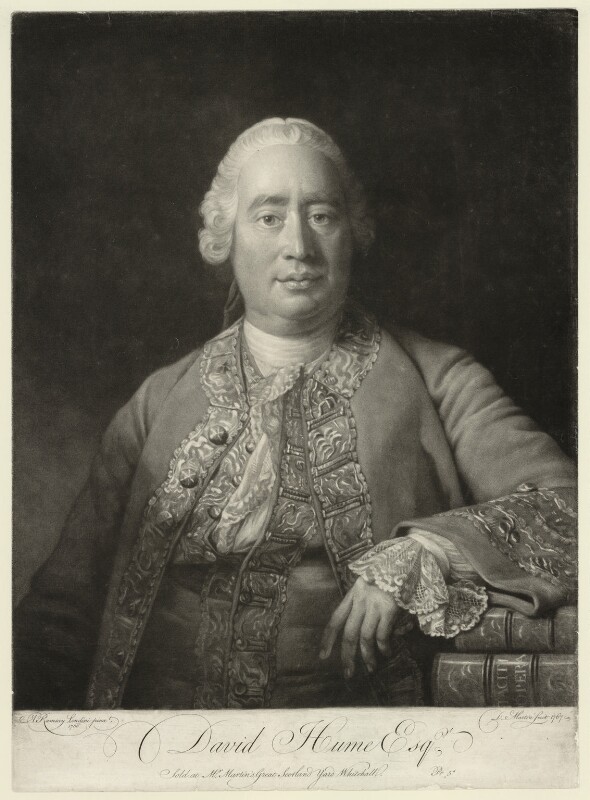

Hume takes a different approach from Rousseau to the story of liberty unfolding in human history. In both the Treatise on Human Nature and An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, he rejects Rousseau’s starting point of humanity’s metaphysical status in the state of nature, with its sharp distinction between the free actions of human beings and the determined actions of other animals in nature. Hume presents what philosophers have characterized as a compatibilist theory of freedom where humans are part of the network of causation in nature, but nevertheless can act under certain circumstances with free will properly understood.[5] This philosophical starting point has important implications for the story of liberty that Hume tells in his Essays and A History of England.

In contrast to Rousseau’s hypothetical history of the fall from freedom in the state of nature, Hume views the actual history of humankind as a perpetual struggle between authority and liberty. Liberty must be sacrificed to bring order to society. But this sacrifice “can never, and perhaps ought never, in any constitution, to be quite entire and uncontrollable.” A society is free not because it is under a General Will authorized by the will of each citizen as it was for Rousseau, but because it operates free of arbitrary coercion under known and settled laws. Free governments, Hume argues, are those that partition power among several members who “in the usual course of administration, must act by general and equal laws known to all members of society.” (Hume, 1987: 41)

According to Hume, this liberty under the law is the “perfection of civil society.” (Hume, 1987: 41) As seen through the lens of English history, the story of liberty is a complex one that rejects Machiavelli’s idea that there are cycles in history mapping out the rise and fall of republics based upon the virtue built into their institutions. Similarly, he discounts that there ever was an ancient constitution upon which civil and political liberty rested or the enlightenment idea that material and moral progress is inevitable. He agrees with other enlightenment thinkers that rule of law is part of the civilizing force of manners and morals working throughout Europe but does not believe that it is inevitable. Events can take place that threaten the stability of government and freedom under law. Under this understanding of a free society, Hume declares in Volume VI of the History of England that “it may justly be affirmed, without any danger of exaggeration, that we in this island, have ever since enjoyed, if not the best system of government, at least the most entire system of liberty, that ever was known amongst mankind.” (Hume, 1983 VI: 531; see also Livingston 1998: Chapter 10; Miller 1981: Chapter 7; McArthur 2007, Chapters 5 and 6)

Integrated into his arguments about constitutional and legal development in England is a rethinking of the role played by commerce and individual self-interest in human affairs. Rejecting the ancient idea that commerce and self-interest necessarily make a free and martial people weaker by corrupting their morals, a notion that Rousseau accepted, Hume argues that the opposite is the case. According to “the common course of human affairs,” the greatness of a state and the happiness of a people are linked together through trade and manufacturing. By rousing men from their natural indolence, commerce and trade encourage individuals to desire more things and to work harder to improve their conditions and transform from the bottom up the social and economic foundations upon which rest a society’s prosperity. (see Hume 1987, “Of Commerce”) Other unintended consequences follow from the changes fostered by exchange and commerce throughout a society. In volume III of A History of England (1983 III: 76), Hume uses this argument to explain the decline of the power of the landed aristocracy in the late middle ages and the rise of more regular forms of government and freedom under the law. Adam Smith would later capture the essence of Hume’s argument in chapter 4 of Book III of the Wealth of Nations: “commerce and manufactures gradually introduced order and good government, and with them, the liberty and security of individuals, among the inhabitants of the country, who had lived before almost in a continual state of war with their neighbours, and of servile dependency upon their superiors.” (Smith, 1981: 412) Far from intensifying bonds of dependency in human history as Rousseau claimed, Hume and Smith argue that commerce and manufacturing propel the story of liberty forward in the modern world.

Conclusions

For Rousseau, human history is a dialectical process where the expanding productive capacities of human society are accompanied by a loss of liberty for the individual. We are born free in nature but become unfree with the evolution of human civilization. As society grows wealthier, individuals grow more miserable and unfree. His story ends with an appeal to rethink the social order and establish new conditions for liberty under the rule of the General Will in the modern world. This is nothing short of a call for a revolution on how we think about liberty and how we act in the world. Unfortunately, the General Will is a slippery concept in actual operation. Is the General Will a metaphysical entity that can exist and act in the world through the actions of properly educated citizens, or is it just a great myth, a delusion born of misguided assumptions about the nature of liberty? Is the General Will a solution to the problems of liberty in modern society, or a new form of tyranny being imposed upon individuals by the state and society?

In contrast, Hume’s story about liberty stresses the importance of the evolution of human civilization out of primitive social and economic conditions, and not a state of nature per se. For Hume, humans are not free in nature. They are simply isolated, alone, and poor. History is the story of forging institutions, laws, and manners that restrict the arbitrary power of leaders and unleash the creative actions of private individuals through exchange, markets, and commerce. Where Rousseau’s story of liberty culminates in a new vision of liberty grounded in a General Will, Hume’s story is a cautionary tale about the need to protect the institutions, laws, and manners that have made modern liberty and human prosperity possible. He rejects the idea of a social contract underlying all government, replacing it with arguments about how government is grounded in public opinion through various mechanisms of consent in history. (See Hume, 1987: “Of the Original Contract”) His warnings about the dangers of commercial institutions, such as the public debt or an overregulated mercantile system are extensions of his concerns over abusive authority that threatens to enslave individuals in modern commercial states.[6] How do we know which institutional or economic developments expand our liberties and which threaten them? What is the metric by which we measure these dangers? Such are the intellectual and political challenges that Hume leaves us to face on our own today.

Brief Bibliography

Edmonds, David and John Eidenow. 2006. Rousseau’s Dog: Two Great Thinkers at War in the Age of Enlightenment. New York: HarperCollins.

Hume, David, 1975. Enquiries Concerning Human Understanding and Concerning the Principles of Morals. Third edition. Reprinted from the 1777 edition with Introduction and Analytical Index by L.A. Selbe-Bigge. With text revision by P.H. Nidditch. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Hume, David. 1983. The History of England from the Invasion of Julius Caesar to the Revolution of 1688. In Six volumes. Based upon the edition of 1778, with the Author’s Last Corrections and Improvements. Foreword by William B. Todd. Indianapolis: LibertyClassics.

Hume, David. 1987. Revised Edition. Essays Moral, Political, and Literary. Edited and with a Forward, Notes and Glossary by Eugene F. Miller. Indianapolis: LibertyClassics.

Hume, David. 2000. A Treatise of Human Nature. Edited by David Fate Norton and Mary J. Norton. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Livingston, Donald W. 1998. Philosophical Melancholy and Delirium: Hume’s Pathology of Philosophy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

McArthur, Neil. 2007. David Hume’s Political Thought. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Merrill, Kenneth P. 2010. A to Z of Hume’s Philosophy. Lanham: The Scarecrow Press:

Miller, David. 1981. Philosophy and Ideology in Hume’s Political Thought. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Penelhum, Terence. 2000. Themes in Hume: The Self, the Will, Religion. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Pocock, J.G.A. 1975. The Machiavellian Moment: Florentine Political Thought and the Atlantic republican Tradition. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Riley, Patrick. “Rousseau’s General Will.” In The Cambridge Companion to Rousseau Edited by Patrick Riley. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. 1997. The Discourses and Other Early Political writings. Edited and Translated by Victor Gourevitch. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. 2011. The Basic Political Writings. Second Edition. Translated and edited by Donald A. Cress. Introduction and Annotation by David Wootton. Indianapolis: Haskett.

Shklar, Judith N. 1969. Men and Citizen’s: A Study of Rousseau’s Social Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969.

Smith, Adam. 1981. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Edited by R.H. Campbell and A.S. Skinner. Textual Editor W.D. Todd. Indianapolis: LibertyClassics.

Zaretsky, Robert and John T. Scott. 2009. The Philosopher’s Quarrel: Rousseau, Hume and the Limits of Human Understanding. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Endnotes

[1] Embedded in western political thought are several stories about liberty and how it unfolds in the course of human history that differ from those told by Rousseau and Hume. The civic republican story as found in the work of Niccolo Machiavelli and members of the Atlantic republican tradition chronicled by J.G.A. Pocock sees liberty in terms of a cyclical pattern of the rise and fall of peoples and nations. Wise and virtuous leaders build a nation’s institutions and laws. Liberty is gained through the great actions of peoples and leaders. Liberty is lost through corruption brought on by weakness, negligence, and ill will. The ancient constitution story as articulated by late medieval and early modern writers opposed to modern state building in Europe is basically a conservative one that centers around the idea that certain institutions and laws inherited from an almost mythical past make freedom possible. The job of politics is to protect liberty by defending these institutions and laws from corruption and decline. A third story of liberty sees scientific, moral, and material progress as being the engine which drives liberty forward. For enlightenment thinkers from the Marquis de Condorcet to Karl Marx, material progress was seen as ushering in a new age of freedom, one unimaginable to earlier generations. Citizens make sure that the conditions that make progress possible are protected and expanded. Often this story is linked to an eschatological break with the past where political action ushers in a new age of prosperity and freedom for humankind.

[2] For a fascinating discussion of the interpersonal squabble between Rousseau and Adam Smith, see Zaretsky and Scott (2009) and Edmonds and Eidenow (2006).

[3] For a further discussion, see Shklar (1969).

[4] For a further discussion of Rousseau’s notion of the General Will see Riley (2001).

[5] Much of Hume’s argument about free will and necessity rests upon his innovative theories of moral responsibility, causation, and the operations of the human mind in A Treatise of Human Nature (2000) and his Enquiries (1975). For a discussion of Hume’s notion of free will and compatibilism see Penelhum (2000) Chapter 8 and Merrill (2000).

[6] See the economic essays in Part II of Hume’s Essays (1987).

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.