Liberty Matters

Athenian Republican Institutions and the Quest for a Democratic Rule of Law

Plato did not say “Democracy is the worst form of Government except all those other forms that have been tried . . .” That was Winston Churchill in his November 1947 speech to the UK House of Commons.[1] But Churchill does not claim the thought as his own, and the Eleatic Stranger in Plato’s Statesman says something very similar. So, perhaps Plato did sort of say it. Here is Seth Benardette’s translation:

. . . the regime of the multitude, in turn is in nearly everything weak and has no capacity for any great good or evil, in comparison, that is, to the rest of the regimes. It’s due to the fact that the offices of rule in it have been distributed in small segments over many officeholders. Accordingly, though of all of the regimes that are lawful it has proved to be the worst, it’s the best of all that are unlawful. And though to live in a democracy wins out over all that are intemperate, of those that are in due order, one must live in this least of all (303a-b).[2]

I take it as a given that neither Plato nor Plato’s Socrates thought that any actual regime had managed to be wholly lawful or temperate. In the Republic Socrates refused to say that it is impossible for that to happen, but he admitted that it was a very remote and improbable possibility.[3] And, if one understands the radical improbability of a lawful and temperate regime as an implied premise in the Stranger’s claim quoted above, then the gist of it really does seem quite close to Churchill’s quip. Paraphrased, the argument would be:

P1: Democracies are the best regime to live in if all regimes are unlawful and/or intemperate.P2: All regimes have been and are likely to be unlawful and/or intemperate.C: Therefore, Democracies are the best regimes to live in of all those that have or are likely to exist.

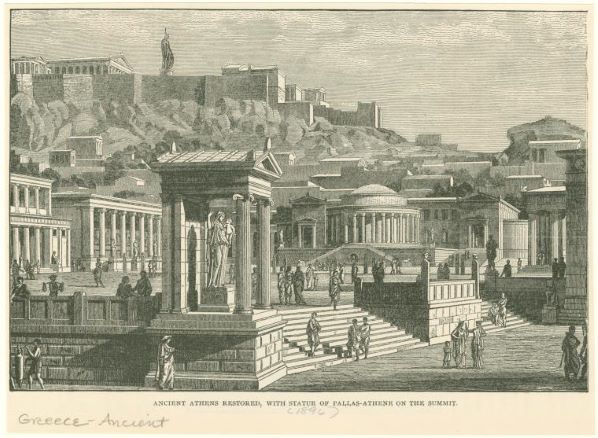

The American Founders knew political history, and a lot of it had happened between the Athenian invention of Democracy and the Eighteenth-century project to create the constitution of the United States. Aristotle and his school had surveyed the constitutions of the ancient Mediterranean and made their extraordinarily well-informed claims about good government; the Romans had invented their republic in light of their understanding of the shortcomings of Athenian institutions; Venice and Florence innovated on Roman and Greek models in hopes of avoiding their fatal errors; and the Glorious Revolution in Britain provided a relatively recent model for a mixed constitution based on the rule of law.

The history of democracies and republics was the image the founders looked to as they imagined stress tests for the emerging shape of the American Constitution. England’s injustices were in the foreground, but the successes and failures of Athens, Sparta, Rome, Venice, Florence, and England were also in play.

It is no wonder that the American Founders rejected Athenian Democracy. Its vulnerabilities and inefficiencies were legion, and they had been well documented since the writing of Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War. On the other hand, many of the remedies that republics have adopted to address those flaws do not seem better than the institutions the Athenians created to support and protect their regime. Some of them seem clearly to be worse. Given this history, I wonder if the Founders’ criticisms of democracy were already known and addressed by the Athenians. I also wonder if the line they drew between democracies and republics is fuzzier than we tend to think it is.

The Roman emphasis on family ties engendered political marriages, divorces, and adoptions that had nothing to do with the sorts of familial bonds that could provide ballast for the ship of state. The Venetian reliance on a wealthy political class engendered centuries of stability even for its poorest citizens, but it looks far more like a model for oligarchy than for a democratic republic. The Florentine Signoria appointed representatives for such short terms that, in retrospect, the de facto transfer of power to wealthy political families seems almost inevitable. And while we now have evidence from the UK that a constitutional monarchy can be stable, in the eighteenth century, the jury was still out.

Athenian Democracy failed, and it was probably destined to fail even if the Peace of Nicias had held, and the Athenians had emerged victorious from the Peloponnesian War. Long before Alcibiades persuaded Athens to steal defeat from the jaws of victory, the Athenian constitution was crumbling. According to Thucydides, Pericles, Cleon, and Alcibiades agreed that even though Athens might call itself a democracy at home, it was a tyranny abroad. Creating it may have been unjust, but failing to preserve it was suicide.

The risks inherent in democracy were not lost on the Fifth and Fourth century Athenians. One can even imagine an alternative history in which Athens, in contradiction to Thucydides’ account of the inevitability of their implosion, moderated its imperial ambitions and buttressed its democratic institutions instead of having to live through a devastating defeat and a bloody tyranny before reestablishing their constitution. Pericles could have lived. Alcibiades could have left sooner.

Before their collapse, one of the institutions the Athenians put into place, albeit for a relatively short period of time, was ostracism. Men like Aristides and Themistocles were heroes to whom the city owed their very existence. (I count at least three times that Themistocles saved Athens in Herodotus’s History.) The ostracism of Themistocles and Aristides was not really punishment, and the things they did to deserve it were not crimes. Their power and influence was so out of proportion with the rest of the Athenians that they could not help but threaten the stability of democracy, so they were ostracized. They were sent away for a while, but not too far away. Their property was preserved, but their political slates were wiped clean. And, most importantly, they were removed from the democratic conversation so that other voices could be heard.

Another institution that bolstered Athenian democracy was Cleisthenes’s division of the city by demes, i.e., tribe and zone. Before Cleisthenes’s reforms, political factions tended to form along family lines. More than a millennium before the influence of the Medici and Pazzi undermined Florentine institutions, Cleisthenes saw that the power of prominent Athenian families had grown into a threat that only promised to worsen. So, he created new factions, or tribes, based on geography rather than family, and he put at the head of each group a mythological hero, rather than a pater familia.

The genius of the deme system didn’t end with the disruption of familial influence, however. The city was also divided into three zones: the city, the farmland/hills, and the seashore. Each deme had an area in each zone. For example, The Erechtheis tribe had a tenth of the urban land, a tenth of the Attic farmland, and a tenth of the Attic coastline. So did the Aegeis, the Kekropis, and each of the other ten tribes. When each tribe rotated into authority in the Prytanis or had to send representatives to the Boule, the citizens within each deme came together from all three zones, and their effectiveness depended upon their agreement. The men of the city, the farmers, and those who fished or shipped or traded by the sea - men who likely had radically different priorities and world-views - had to find common cause. Factions that might naturally be divided according to the interests of urban life, or farming, or seafaring could not easily form outside of one’s tribe. Inside of one’s tribe, alienating oneself from those living in different zones was self-defeating, weakening the influence of their deme in the democratic process.[4]

It is also worth noting here that, contrary to popular opinion, representation was a key element of Athenian democracy. It is true that laws were finally ratified by the direct vote of the Ecclesia, but there was no debate on the Pnyx. Debate happened in the Boule, where representatives from each deme hashed out legislation. Matters of state that could not wait for the Boule were made by the Prytaneis, which was constituted by representatives of one deme rotating in to take that office for just one month a year.

The American Founders did not want to create a direct democracy. But neither did the Athenians, really. All the experiments in democratic/republican government from Solon to the American Founding and up to this moment have sought a scheme that would balance representation with enfranchisement in a way that mitigated against the emergence of powerful individuals or factions that could overpower or undermine the regime. Perhaps someday we’ll find it.

Endnotes

[2] Plato, Plato’s Statesman, 1984, Edited and Translated by Seth Benardete. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[3] 499b

[4] I’m indebted to George Kokkos for our conversations about Cleisthenes reforms and the lessons they offer to contemporary Americans thinking about gerrymandering.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.