Liberty Matters

Liberty and the Mixed Constitution

The Constitution of the United States, according to James Madison, “forms a happy combination” between national and local interests, intended to make it “more difficult for unworthy candidates to practice with success the vicious arts by which elections are too often carried” (Federalist 10). The idea that the best form of government is a mixed constitution, combining elements germane to various different political systems, is an ancient one, as Ioannis Evrigenis expertly shows in his essay.

Significantly, the Latin name Publius is the collective pseudonym chosen by the co-authors of the Federalist Papers to publish their writings — this nom-de-plume being generally understood to be an allusion to Publius Valerius Publicola, the sixth-century-B.C.E. Roman statesman who contributed to overthrowing the monarchy. As consul in the early days of the Roman republic, Publicola fostered the promulgation of laws to forestall a widely feared return of the Etruscan kings.

On one occasion, Publicola famously ordered his lictors to lower the fasces (which is not unlike asking officers or bodyguards to lower their weapons) so as to symbolize his deference towards the citizens’ assembly and dispel any rumors that he was aiming to establish himself as Rome’s new king. Publicola’s gesture reminded the Romans that he was not one of the notorious demagogues who relied on popular support to pursue their own petty personal or factional interest through “vicious arts,” as Madison would put it.

Indeed, the authors of the Federalist Papers often insist on the distinction between two different forms of popular government, illustrating the ways in which they embraced a ‘republican’ constitution rather than a purely ‘democratic’ one. Despite it being often overlooked or forgotten, it is a fact that the word ‘democracy’ never occurs in the Declaration of Independence (1776) nor in the Constitution of the United States of America (1789).

The reason why such an omission is a result of design and not of accident can be sought for precisely in the framers’ skepticism and distrust towards democracy, which in turn is ultimately rooted in their extensive familiarity with ancient Greek and Roman political thought.

In this regard, it is important to keep in mind that any modern analysis of ancient political theory suffers from a sizable degree of ‘selection bias,’ insofar as the vast majority of Greek and Latin sources at our disposal present a view of government that is programmatically hostile towards democracy, so that we rarely (if ever) get to hear the opposing voice of those who support it.

For instance, both Thucydides and Plato — authors crucial to Evrigenis’ argument — are representatives of an Athenian aristocracy that looked with great suspicion upon democratic statesmen (or, in their view, demagogues) like Cleon and Anytus. Both writers operated in a historical environment in which oligarchic coups repeatedly attempted to overthrow the city’s democratic institutions around the late fifth and the early fourth century B.C.E.[1]

While Pericles extensively praises the Athenian institutions (serving as a contrast to Sparta’s oligarchy) in his Funeral Oration (Thuc. 2.39),[2] Thucydides himself praises Pericles as the leader who was able to successfully control the crowds instead of being influenced by their ever-changing moods, thereby transforming the city’s nominally democratic institutions into a de facto autocratic government: ἐγίγνετό τε λόγῳ μὲν δημοκρατία, ἔργῳ δὲ ὑπὸ τοῦ πρώτου ἀνδρὸς ἀρχή (Thuc. 2.65.9), or, in Thomas Hobbes’ English version, “It was in name a state democratical, but in fact a government of the principal man.”

In the fourth century, Isocrates offers a more nuanced assessment of Athenian democracy, arguing that the tyranny of the majority loathed by Thucydides and Plato was by no means the government form originally intended by the city’s founding fathers, Solon and Cleisthenes: they “did not establish a polity [...] which trained the citizens in such fashion that they looked upon insolence as democracy [ἡγεῖσθαι τὴν μὲν ἀκολασίαν δημοκρατίαν], lawlessness as liberty, impudence of speech as equality, and license to do what they pleased as happiness, but rather a polity which detested and punished such men and by so doing made all the citizens better and wiser”(Isocrates, Areopagiticus 20).[3]

To the classical thinkers and historians mentioned by Evrigenis one might add Polybius, the second-century Greek writer who, in the sixth book of his Histories, attributes the unique magnitude and resilience of the Roman dominion to the development of a mixed (μικτή) constitution in Republican Rome. Polybius distinguishes three ‘simple’ forms of government: monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy.

According to him, each of these three kinds of constitution is bound to be short-lived if used in its pure form, as each of them tends to degenerate into its ‘corrupted’ version. Thus, monarchy is soon replaced by tyranny, aristocracy by oligarchy, and democracy by that most degraded of all political aberrations, ochlocracy (or mob-rule).

In Polybius’ view, the long-lasting rule and stability of Rome, which for centuries has avoided the endless cyclical decay (ἀνακύκλωσις) of one government form into another, is primarily owed to the Roman constitution’s way of mixing elements of all three systems into one state (“a happy combination,” as Madison would put it).

In the Roman republic, according to Polybius, the consuls represent the monarchical element, the senate embodies the old aristocracy, and the popular assemblies give the citizenry a democratic voice. Thus, political power is shared among the three governing bodies, and each of the three materializes a limit to the authority and influence of the other two.

This Roman system of checks and balances, along with its Polybian elucidation, was bound to exercise considerable influence on those early modern political thinkers that the framers often drew upon in their own constitution-making efforts. Montesquieu, in particular, directly quotes Polybius in his Pensées: “je renverrai à Polybe, qui a admirablement bien expliqué quelle part les consuls, le Sénat, le Peuple, prenaient dans ce gouvernement” (“I shall go back to Polybius, who has admirably explained what role the consuls, the senate, and the people played in this government”).[4]

In his Spirit of Laws (11.17), a treatise very familiar to the constitutional framers, Montesquieu emphasizes the importance of the senate in the Roman republic’s balance of powers, and cites Polybius in the same breath: “La part que le sénat prenoit à la puissance exécutrice étoit si grande, que Polybe dit que les étrangers pensoient tous que Rome étoit une aristocratie” (“the role played by the senate in the executive power was so great that, according to Polybius, all foreign people considered Rome to be an aristocracy”). The passage he refers to here is Polyb. 6.13.8-9:

If one were staying at Rome when the consuls were not in town, one would imagine the constitution to be a complete aristocracy: and this has been the idea entertained by many Greeks, and by many kings as well, from the fact that nearly all the business they had with Rome was settled by the Senate.[5]

Interestingly enough, Montesquieu omits the Polybian statement limiting this account to time periods in which the consuls were away from Rome. As a result, the preeminent powers of the senate appear, for the French philosopher, to be an even more inherently constitutional feature of the Roman republican system than Polybius makes it sound. Might that be because, not unlike Thucydides and Plato, Montesquieu is wary of the dangers of unmixed, unbridled democracy?

Democracy, according to Montesquieu, is subject to corruption in either of two ways: i.e., through “the spirit of inequality” or “the spirit of extreme equality” (Spirit of Laws 8.2). The former prevails when citizens place their own individual interest over the common good of their country and seek political power at the expense of their fellow citizens. The latter takes root when the citizens, no longer content with being equal before the law, seek to become equal in all aspects of their lives and thereby cease to respect institutional authority.

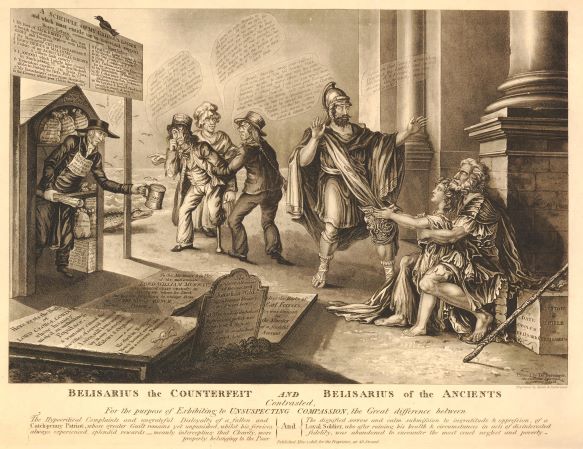

It is precisely this kind of political milieu, pervaded by the “spirit of extreme equality,” that paves the way for the ascent of unscrupulous demagogues: “Men of factious tempers,” in Madison’s view (Federalist 10), “of local prejudices, or of sinister designs, may by intrigue, by corruption, or by other means, first obtain the suffrages, and then betray the interests of the people.” Unrestrained democracy, in other words, is prone to degenerating into demagogy.

To be sure, as Evrigenis points out, it would be misguided to claim that the US was not founded upon the principles of popular government. However, far from being interchangeable notions, ‘republic’ and ‘democracy’ are utterly distinct in terms of the framers’ value judgment. Indeed, they viewed democracy as the source of several threats and dangers to freedom. “Why a Republic” then, Evrigenis asks, rather than a democracy? For the framers, the central purpose of the government is to grant citizens the threefold rights to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

To that end, the Constitution establishes the rule of law and lays down clear limitations to the scope of government, so as to protect the rights of individual citizens from any abuses of power, as well as from each other. As a consequence, the framers’ constitutional efforts went to great lengths to make sure that the federal government was a republican one, in the Polybian sense, and thereby sheltered from what they perceived to be the hazards of mob-rule democracy.

References

Harris, E. (1992) Pericles’ Praise of Athenian Democracy. Thucydides 2.37.1. “Harvard Studies in Classical Philology” 94, pp. 157-167.

Kagan, D. (1991) The Fall of the Athenian Empire. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Norlin, G. (1928) Isocrates, with an English Translation in Three Volumes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Shuckburgh, E. (2013) The Histories of Polybius. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press (first published in 1889).

Endnotes

[1] See Kagan 1991.

[2] See Harris 1992.

[3] Translation: Norlin 1928.

[4] Montesquieu, Pensées #1672 (translation mine).

[5] ἐξ ὧν πάλιν ὁπότε τις ἐπιδημήσαι μὴ παρόντος ὑπάτου, τελείως ἀριστοκρατικὴ φαίνεθ᾽ ἡ πολιτεία. ὃ δὴ καὶ πολλοὶ τῶν Ἑλλήνων, ὁμοίως δὲ καὶ τῶν βασιλέων, πεπεισμένοι τυγχάνουσι, διὰ τὸ τὰ σφῶν πράγματα σχεδὸν πάντα τὴν σύγκλητον κυροῦν. Translation: Shuckburgh 2013.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.