Liberty Matters

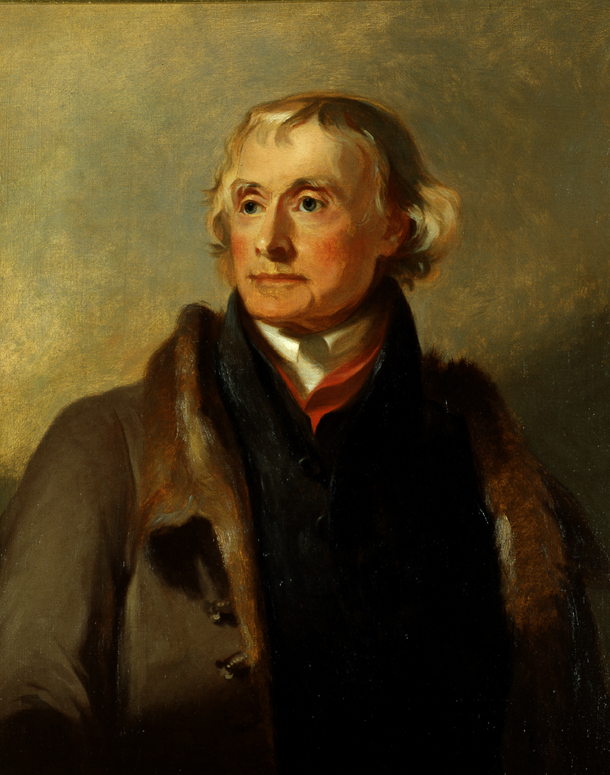

Neither a Federalist nor an Anti-Federalist: Thomas Jefferson’s Ambiguous Early Relationship to the U.S. Constitution

“How do you like our new constitution?” Thomas Jefferson wrote inquisitively to John Adams from Paris in November 1787.[1] Recently, just two months after the Constitutional Convention adjourned in Philadelphia, Jefferson had received copies of the new Constitution from multiple sources including George Washington, James Madison, Benjamin Franklin, and Adams, via Adams’s son-in-law William Smith. As he sought Adams’s opinion, he shared his own views with a variety of correspondents over the next several months. Eventually, Jefferson’s views of the Constitution evolved. But not until his famous conflict with Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton over the proposal for a Bank of the United States in 1791 did Jefferson begin to study closely and think about a mode of interpreting the Constitution. In short, his Constitutional thinking moved from general dissatisfaction from afar, to a more mixed, ambivalent (and seemingly uninterested) view, and then finally toward his doctrine of strict construction.

Jefferson was lukewarm toward the Constitution initially. In his letter to Adams, he confessed “there are things in it which stagger all my dispositions to subscribe to what such an assembly has proposed.” He thought the House of Representatives would be inadequate and that “Their President seems a bad edition of a Polish king” who, through reelection “is an officer for life.” In short, Jefferson believed the Convention had overstepped. “I think all the good of this new constitution might have been couched in three or four new articles to be added to the good, old, and venerable fabric, which should have been preserved even as a religious relique.”[2] That same day, November 13, 1787, Jefferson wrote also to William Smith thanking him for enclosing a copy of the Constitution since he was not sure if it came through Smith or Adams and asked him “to place them where due.” As to the document itself, Jefferson acknowledged “There are very good articles in it: & very bad. I do not know which preponderate.” From that point Jefferson went on to make comments that his opponents seized on for years as evidence of his alleged radicalism: “God forbid we should ever be 20 years without such a rebellion,” a reference to Shays’s Rebellion. Jefferson thought the Convention “has been too much impressed by the insurrection of Massachusetts: and in the spur of the moment they are setting up a kite to keep the hen-yard in order.”[3]

These were Jefferson’s first impressions. In December 1787, upon further reflection and having received a detailed report on the Constitution and the Convention’s work from James Madison in late October, Jefferson offered more considered objections and reservations. He liked the separation of government into branches and thought it would aid in maintaining a national government without regular references to the state legislatures. “I am captivated by the compromise of the opposite claims of the great & little states,” he wrote, and declared he was “much pleased” by the adoption of voting by persons rather than voting by states. “There are other good things of less moment. I will now add what I do not like,” as he shared his familiar litany of items with Madison. Chief among his objections was the lack of a bill or rights “providing clearly & without sophisms” for fundamental rights. He rejected James Wilson’s arguments that a bill of rights was unnecessary to protect against powers that were not specifically reserved to the new government. After all, “a bill of rights is what the people are entitled to against every government on earth.” Jefferson’s second main objection—a “feature I dislike, and greatly dislike,” should Madison miss the message—was the wholesale abandonment of rotation in office, particularly as it concerned the presidency. Jefferson believed that experience showed “that the first magistrate will always be re-elected if the Constitution permits it. He is then an officer for life.” After providing additional discussion and examples of Polish kings, he admitted to Madison that he could “not pretend to decide what would be the best method of procuring the establishment of the manifold good things in this constitution, and of getting rid of the bad.”[4] He named future amendments and a reconsideration by another convention—after determining during ratification what the people disliked and what they approved generally in the Constitution—as two possibilities.

Perhaps aware that Madison might not share his views, and that events across the ocean might have overtaken his ability to follow them in a timely way, Jefferson told his friend that he had shared his list of likes and dislikes “merely as a matter of curiosity, for I know your own judgment has been formed on all those points after having heard everything which could be urged on them.” After sharing with Madison a version of his belief that Americans had overreacted to Shays’s Rebellion, a self-aware Jefferson apologized: “I have tired you by this time with my disquisitions.”[5]

Jefferson wrote a fourth letter, in February 1788, to Alexander Donald, in which he proposed a novel means of both ratifying and securing his desired amendments. Jefferson wished that “the nine first conventions may accept the new constitution, because this will secure to us the good it contains, which I think great and important. But I equally wish, that the four latest conventions, which ever they be, may refuse to accede to it, till a declaration of rights be annexed.” Jefferson believed “This would probably command the offers of such a declaration, and thus give to the whole fabric, perhaps as much perfection as any one of that kind ever had.”[6] As was his custom, Jefferson rehearsed for Donald his dissatisfaction with the absence of a bill of rights and the re-eligibility of the president.

More than a year later—with Jefferson still serving in Paris and the Constitution ratified across the nation—he replied to his old friend Francis Hopkinson who wanted to ascertain Jefferson’s politics in the ratification struggle. At considerable length, Jefferson reflected on how his position had been formed early and held consistently despite his being always out of step with events on the ground, owing to the months of delay in receiving and conveying letters. To Hopkinson, Jefferson expressed some ambivalence and stated emphatically that he was not aligned with either the Federalists nor the Anti-Federalists, despite what Hopkinson had apparently been told. “You say that I have been dished up to you as an antifederalist, and ask me if it be just.” He derided the notion that his own allegiance was “worthy enough of notice to merit citing,” but then happily explained himself to Hopkinson.[7]

“I am not a Federalist,” he asserted, “because I never submitted the whole system of my opinions to the creed of any party of men whatever in religion, in philosophy, in politics, or in anything else where I was capable of thinking for myself.” Then he penned what became an oft-quoted line: “If I could not go to heaven but with a party, I would not go there at all.” Thus, “I protest to you that I am not of the party of federalists. But I am much farther from that of the Antifederalists,” he wrote. Jefferson proceeded to suggest how neither of these “parties” properly captured his full views on the Constitution and thus why neither label was accurate. “I approved, from the first moment, of the great mass of what is in the new constitution,” he continued, and then listed the positives he had laid out for Madison and other correspondents. “What I disapproved of from the first moment also was the want of a bill of rights to guard liberty against the legislative as well as executive branches of the government.” In addition, Jefferson reiterated his objection to executive re-eligibility. Recapping his letter to Alexander Donald, he exclaimed that his “first wish was that the 9. first conventions might accept the constitution….and that the 4. last might reject it.” Here, Jefferson remarked that he “was corrected in this wish the moment I saw the much better plan of Massachusetts and which had never occurred to me,” a reference to the practice first utilized by the Massachusetts Convention of voting to ratify and also recommending a list of amendments to the first new congress. Jefferson believed that of his two great objections to the Constitution, most Americans shared his displeasure at the absence of a bill of rights, but that he was in the minority when it came to concern over Presidents being able to serve repeated terms. And given his respect for Washington, he would not wish to see that clause changed since “our great leader, whose executive talents are superior to those I believe of any man in the world…But having derived from our error all the good there was in it I hope we shall correct it the moment we can no longer have [Washington] at the helm.”[8]

“These…are my sentiments, by which you will see I was right in saying I am neither federalist nor antifederalist; that I am of neither party, nor yet a trimmer between parties.” Jefferson also was proud that he made his assessment of the Constitution early and stuck to it. He had expressed “my opinions within a few hours after I had read the constitution, to one or two friends in America. I had not then read one single word printed on the subject. I never had an opinion in politics or religion which I was afraid to own,” he told Hopkinson, and then closed with a self-deprecating apology for having written “an egotistical dissertation.”[9]

Each of these letters was written from France where he faced the challenges of distance and the time-lag of communication. In fact, Jefferson did not return to Virginia until November 1789, at which point he learned he had been nominated by George Washington as Secretary of State and approved by the Senate. s He was being overtaken by the fast-moving events of the French Revolution as he was departing Europe. Upon his arrival in the United States he was quickly pressed into service in Washington’s cabinet and besieged by the duties of the job, caught up in his return to a country changed dramatically since he last lived there in 1784. As Jefferson suggested to Hopkinson, it seems he formed his opinion of the Constitution very quickly, repeated those views consistently, and left his mind unchanged—not that the Constitution took up much of his mental space. Not directly involved in the drafting or ratification of the Constitution, it may not have been as interesting to Jefferson as were other matters at hand. As Mary Sarah Bilder notes, “His perspective had been dominated by French political rhetoric…He came to the Constitution as a reader. His information about American constitutional politics had been filtered by correspondents and visitors.” Upon his return other matters grabbed his attention and he was “uninterested in the Constitution.” When asked about studying the law Jefferson referred inquirers to local laws in Virginia. He tended to cite natural rights or the broader American legal tradition as justification for laws, ignoring the Constitution which he rarely referenced. Furthermore, “Jefferson did not interpret the Constitution as supplanting the pre-1787 constitutional structure with which he was familiar.”[10]

In fact, the first time a constitutional issue arose in the new government—over Hamilton’s funding and assumption programs—Jefferson famously played peacemaker, giving Hamilton a full hearing as the Treasury secretary “walked him back and forth for two hours in front of the President’s house” and then he brought Hamilton and Madison together for the dinner table bargain that exchanged southern votes for Hamilton’s program in return for locating the permanent capital on the Potomac.[11] Not until the debate over Hamilton’s national bank bill in 1791 did things change. Mary Bilder suggests that this was the first time Jefferson, increasingly concerned over Hamilton’s actions, intrigues, and influence, showed real interest in the Constitution and the first time he really began to dig into Madison’s manuscript notes on the work of the Convention. Only then, and from that point forward, did Jefferson—now in the throes of the great party struggles of the 1790s—show real interest and curiosity in the Constitution and its creation. For him, “the bank bill hinted at potential contemporary political usefulness of the Notes,” writes Mary Bilder.[12]

Jefferson’s constitutional thinking started late and was marred by distance and distraction initially. But he got up to speed quickly and his eventual advocacy of strict construction of the Constitution fit seamlessly into his emerging political vision and became a crucial component of the party ideology that separated Jeffersonians from Hamiltonians.

Endnotes

[1] Thomas Jefferson to John Adams, November 13, 1787 in Merrill Peterson (ed.), Jefferson Writings (New York: Library of America, 1984), p. 913. For excellent overviews of this subject see the works by R.B. Bernstein cited in note 11 below. For a broader treatment see Jeff Broadwater, Jefferson, Madison and the Making of the Constitution (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019).

[2] Jefferson to Adams, pp. 213-214.

[3] Jefferson to William Smith, November 13, 1787 in Jefferson Writings, pp. 910-911.

[4] Jefferson to James Madison, December 20, 1787 in Jefferson Writings, pp. 915-917.

[5] Jefferson to Madison, p. 917.

[6] Jefferson to Alexander Donald, February 7, 1788, Jefferson Writings, p. 919.

[7] Jefferson to Francis Hopkinson, March 13, 1789, Jefferson Writings, p. 940.

[8] Jefferson to Hopkinson, pp. 941-942.

[9] Jefferson to Hopkinson, p. 942.

[10] Mary Sarah Bilder, Madison’s Hand: Revising the Constitutional Convention (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2015), pp. 202-204.

[11] R. B. Bernstein, “Thomas Jefferson and Constitutionalism,” in Francis D. Cogliano (ed.), A Companion to Thomas Jefferson (Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing, 2012), p. 427. See also R. B. Bernstein, Thomas Jefferson (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), pp. 70-76 and p. 86-88.

[12] Bilder, Madison’s Hand, p. 208.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.