Liberty Matters

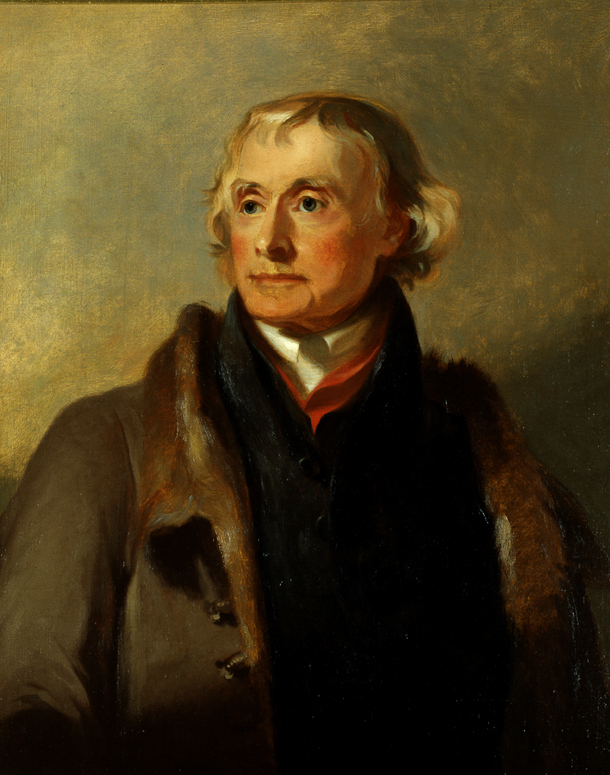

Fixing Thomas Jefferson’s Understanding of the Constitution: A Reply

I am grateful to my colleagues on this project for the thoughtful, supportive, and helpful comments on my initial essay. Christine McDonald rightly emphasizes—and does so with specific details of the distance between Paris and the United States and the time it took for news to travel—the sheer impact of Thomas Jefferson’s far removal across the Atlantic and how that vast distance made Jefferson’s absence from the ratification debate near total. As she underscores, the fact that Jefferson was so far away and the time lag between when news left one shore and reached the other made it unavoidable that Jefferson would be well behind the curve of what was transpiring in the ratification debate in the United States. Therefore, it is not the least surprising that Jefferson found it hard to keep up with events on the ground in the fast-moving ratification contest from his post in Paris, and that those events and his reactions to them existed in a time warp. Her emphasis on distance in space and time adds valuable context to Jefferson’s halting, fragmented initial comments on the Constitution and suggests logical reasons for his frustration and subsequent disengagement.

McDonald’s point about his absence and physical distance in the ratification debate also speaks to a point raised by Hans Eicholz in his keen and probing question asking “What then did Jefferson actually count as ‘Antifederal?’” The question is complex in part because of the role of distance in explaining Jefferson’s absence from the ratification debate. Not only did it mean, as McDonald notes, that he was late in getting and processing information, it also kept Jefferson from being intimately connected to the rhythms and patterns of the ratification debate. This meant that the issues, terms, and definitions unfolding in the debate over the Constitution were not ones that Jefferson could be familiar with, certainly not in real time. Thus, Jefferson’s frame of reference was not the same as the participants who engaged in the newspaper contest and in the state ratifying conventions. The intricacies—and the occasional shifts—of what constituted Federalist and Anti-Federalist positions and arguments understandably escaped his grasp. So, what others might term the “Anti-Federal” mindset or position was not necessarily the same as what Jefferson understood it to be. It would be somewhat akin to reading from an out-of-date textbook: the terms might be familiar but the meanings and significance had changed.

I take Eicholz’s clarification about how Jefferson did not lack prior views on applying fundamental law, but rather shared the same perspective others trained in the law might have held as a foundational tenet prior to the Constitution, which had shaken up the board quite a bit. And as both of my interlocutors noted, Jefferson’s constitutionalism did become a crucial part of his political vision. But we might say that his vision was shaped more by the events of 1798 than by those of 1788. Or, more broadly, by the events of the 1790s than by those of the 1780s. While Jefferson was far removed from the ratification contest, he was as deeply involved as anyone in the fierce partisan political contests of the 1790s in which everything seemed to be open to contestation—including, perhaps even especially—the meaning and mode of interpreting the Constitution. Jefferson’s constitutionalism emerged and became a crucial part of his vision and his legacy. But it happened gradually, and for him the ratification contest seems to have been far less significant and foundational than it was for some others.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.