Liberty Matters

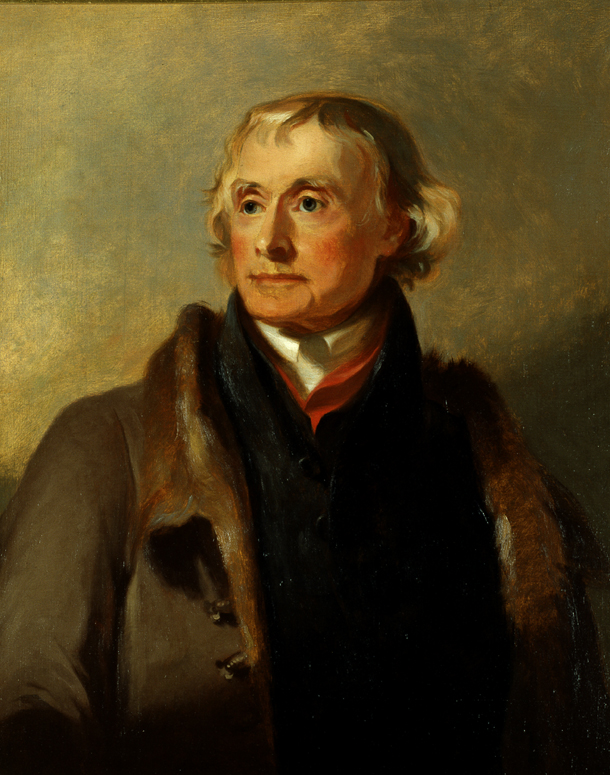

Early v. Later Thomas Jefferson: Perspectives on Religion and Slavery

Despite the tonnage of books, essays, articles and other publications written about Thomas Jefferson—from his lifetime down to ours—there is always room for more because Jefferson himself remains an inexhaustible source for inquiries into his past as well as the American past. This set of papers teems with examples.

Christine McDonald’s essay digs into the question of Jefferson’s personal religious beliefs and practices and calls into question the assumptions often made about Jefferson—that he was a Deist, or an atheist, hostile to religion, or without belief himself. These assumptions are either incorrect, exaggerated, taken out of context or otherwise off the mark. In other words, they are at best incomplete. McDonald examines the last days of Jefferson’s life in summer 1826 to look for a better understanding. We know that his public statements and actions made clear his unbending commitment to the separation of church and state and to the absolute importance of the individual’s freedom of conscience in personal religious matters. But what were Jefferson’s private religious beliefs? Despite the suggestiveness of the story of his final days that McDonald recounts, the answers remain inscrutable. “Jefferson’s faith was between him and his God,” she observes as she quotes Jefferson on the matter in 1813 when he wrote that his own religious beliefs were “a subject on which I have ever been most scrupulously reserved.”

Was Jefferson surreptitiously religious himself? At the time of his death or in the last years of his life? The answers remain elusive yet tantalizing, and McDonald’s suggestive essay makes it clear that his beliefs seem to have evolved over his life and may well have been yet another area of Jefferson’s life where myth obscured reality. What might Jefferson have said to his clergyman-neighbor, Fredrick Hatch, had they talked in those last hours? McDonald provides a deep dive into the primary source record and a close reading of key works. But I’m curious to know what other scholars who have looked at Jefferson and religion (Paul Conkin, Edwin Gaustad, and others) have concluded—not about the potential conversation with Hatch but about the larger issues. And I wonder how Kate Carte’s recent book on religion and the Revolution might shed light on the broader context of religion in Jefferson’s age.

Both Hans Eicholz and Cara Rogers Stevens probe the uber-controversial topic of Jefferson and slavery in their papers. As I read them, it seems that Eicholz surveys the conundrum of Jefferson’s moral opposition to slavery, concedes the compromises with slavery that Jefferson made, and poses an important, fundamental, and fascinating question of “why he ever held his original commitments to begin with.” Eicholz traces Jefferson’s early convictions that slavery in any circumstance was morally repugnant. But he also notes the reality of Jefferson’s accommodation on the issue, writing “Ultimately, Jefferson did not follow through with those early commitments in his own life, but he also never wavered from the conviction that enslavement in all forms was an evil.” By looking back to the pre-1780 years in search of answers, his paper helpfully suggests, we may find some clarity on Jefferson’s perspective.

In many respects, Stevens’s well-documented and vigorously-argued paper (drawn from her superb new book on the subject) picks up exactly where Eicholz leaves off. Her work offers some answers and fleshes out the potential inherent in Eicholz’s suggestion that Jefferson’s opposition to slavery was fixed early in his career and shifted only later. Stevens confirms Eicholz’s sense that looking to Jefferson’s pre-1780s life enables us to track his initial opposition to slavery, overtaken—as his career unfolded—by a necessary softening and hedging of those positions. Context is everything in discerning Jefferson’s views. Stevens asks rhetorically if Jefferson could have done more to oppose slavery. “Absolutely,” she writes. “And, if he had, we might look more favorably on him today than we do—that is, if his risk-taking did not scuttle his political career before he was able to become president.” 17th and early 18th century Virginia, she notes, “was a place extremely hostile to emancipators.” Context again is key: “Jefferson attempted to act within the boundaries of what was acceptable at the time, doing less than some others, and more than most.”

What we can never know is what might have become of Jefferson’s anti-slavery views—and more importantly, his actions—had he chosen a career path outside of politics. For example, had he chosen to become a college professor like his mentors William Short and George Wythe, or if he had chosen a career in diplomatic service or in local government and not aspired to become a national political figure, might he not have felt it necessary to soft-pedal or abandon his earlier opposition to slavery as articulated here by both Eicholz and Stevens? Might he have retained—or even extended—the anti-slavery positions he boldly took in the 1760s and 1770s? That is an unanswerable question. But it is, thanks to these papers, at least a plausible one given the ways Stevens and Eicholz document Jefferson’s writings against slavery until his pivot.

Answers may be elusive, but well-framed, contextualized questions such as those posed here in these suggestive essays by McDonald, Eicholz, and Stevens provide a portal of entry for further study.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.